Beirut-based writers and curators Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti were invited by tranzit.hu, in relation to its activity on exhibition histories, 1 to present the documentary and archival exhibition Cartography of Artist Solidarity – Narratives and Ghosts from the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, 1978. The Budapest chapter of the exhibition is the third iteration after it was presented at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) in 2015 and at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin in 2016, and it is planned to travel to other venues as well. 2

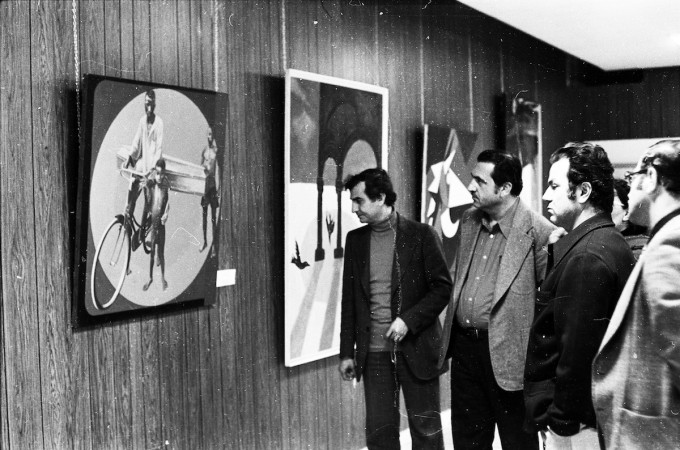

The project starts from unraveling the story and the context of the large-scale International Art Exhibition for Palestine, 1978 that took place at the Beirut Arab University, at a time of civil war in Lebanon. It was organized by the Plastic Arts Section, under the Office of Unified Information, of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which, overall, also undertook cultural events as a means for communicating and shaping discourse around the Palestinian cause. 3 The exhibition that featured around 200 works, donated by nearly 200 artists from 30 different countries, 40 years later, however, was already forgotten. Khouri and Salti not only uncover the story of this particular exhibition, based on scarce documents, oral history, and subjective memories—as they say—through “detective work” and writing a “speculative history,” but they also excavate and interconnect the various solidarity struggles and anti-imperialist movements or actions of the time, initiated across the world, such as the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende, the internationally touring exhibition Art Contre/Against Apartheid, or the Salon de la Jeune Peinture in Paris. The solidarity exhibition with Palestine moreover was also conceived as the foundation of a museum that would operate as a “museum in exile” until it could return to a free and democratic Palestine. Consequently, the exhibition became itinerant itself, and works from the collection traveled to Oslo, Tokyo, and Tehran between 1978 and 1981.

Hungary, as a member of the Eastern Bloc and the anti-imperialist movement, supported the Palestinian struggle as per the official, state-sponsored solidarity. Eastern Europe and its cultural diplomacy thus denoted a particular position amongst other solidarity movements that were mostly grassroots and self-organized in the so-called capitalist countries, such as France or Japan. In conjunction with the exhibition at tranzit.hu, a Free School for Art Theory and Practice seminar on cultural diplomacy was also organized that investigated precisely this aspect of art events initiated by the state. As Zsuzsa László (tranzit.hu) underlined, thus far research on Eastern European exhibition histories has mainly concentrated on the underground, alternative scene, while examining the official, state-sponsored level, as the other side of the same coin, is just as much important. In this light, Ljubljana-based curator Bojana Piškur was also invited to the Free School to present art events organized through the official cultural policy of Yugoslavia.

The exhibition in Budapest also expands with Zsuzsa László’s research that attempts to map solidarity struggles in Hungary, both in the underground and the official scene, as well as their overlaps, with a special focus on how these practices connected to the solidarity movement for Palestine. As part of elaborating local connections, artist Andreas Fogarasi was invited to create a new work in the exhibition that reflects on the participation of the only Hungarian artist at the 1978 exhibition in Beirut, Gyula Hincz (1904–1986), who, as an “official artist,” received several state commissions at that time.

Eszter Szakács: Can you say a few words about the larger and the more immediate context of your project? How does it connect to current research on the history of modern art in the Arab world? You mentioned during the Free School seminar that a so-called “museum fever” in the Persian Gulf likewise propelled you to start this project. Also, how did the two of you come together for this research?

Rasha Salti: Kristine and I were introduced and brought together in 2008 by Walid Raad, a Lebanese artist who works in New York. At that time, he was working on a project, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: A History of Art in the Arab World, that addressed the history of Lebanese modern art, a subject about which we both had some knowledge and were interested in. The larger context of our research is indeed a reawakened interest in the modern period at auction houses and art fairs, mostly Art Dubai. There were also many auctions by Christie’s and Sotheby’s where modern art was sold. It was collectors and also institutions in the Gulf who were acquiring, as well as museums around the world that would eventually do so, such as the Tate Modern, MoMA in New York, and Guggenheim

Kristine Khouri: Sotheby’s and Christie’s, and later Bonham’s in 2005 and 2006 set up offices in the Gulf, and that really took it to the next level of interest in modern art in the Arab World, in addition to the museums that were emerging in the Gulf.

RS: Working together with Kristine as well as Walid, Kristine and I realized that we have a desire to continue doing research. So, we formed a Study Group (registered as non-profit association), the History of Arab Modernities in the Visual Arts Study Group, with which we hoped to appeal to art historians, but only a few accepted the invitation to collaborate with us.

The 1990s and 2000s, witnessed a proliferation (and celebration) of research-based practice, mostly by artists rather than curators. There are interesting initiatives like the Arab Image Foundation (Beirut based), or Casa Mémoire (Casablanca based). There is a growing number of these initiations; it seems we are also part of a phenomena. On the other hand, we also realized at the moment we started our Study Group that we connected to other networks such as the Red Conceptualismos del Sur; so, I don’t think this phenomenon is exclusive to the Arab world.

ESz: Yes, it can also be connected to Zsuzsa László’s work in tranzit.hu’s Parallel Chronologies project that tries to map exhibition histories in Eastern Europe in the Cold War era. Going back to the very start of your project, the catalog you found of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine (Beirut, 1978) was the point of departure and the foundation from which you started your research. This exhibition was not only unknown or forgotten before, but also its documentation and remnants were scattered, as the building that housed the collection after the exhibition took place in 1978 was shelled during the Israeli army’s siege of Beirut in 1982. When you discovered the catalog and learned about the exhibition, why did it strike you immediately as significant?

RS: In the beginning, when we came across the catalog, we did not think that our research would lead to an exhibition, we thought we would publish articles and papers for conferences. It was really intriguing that there was an exhibition of this scale, taking place in the 1970s, in the time of civil war in Lebanon. Thus, there was a history that we were not aware of, and most people were not either. Step by step, after a few years, when we met the then director of MACBA in Barcelona, Bartomeu Marí, and Walid Raad also, suggested that our research should transform into an exhibition.

ESz: Thus far, the three iterations of the project (at MACBA, HKW, and tranzit.hu) have been slightly different, with various focuses and additional, localized materials. At the seminar, you walked us through the first two chapters. The exhibition you presented first at MACBA also connected to the larger themes of exhibition histories and “decolonizing the museum.” It was extended at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin with reflections on the canon as well as an attempt to locate pre-1989 solidarities, beyond the state-sponsored ones established by the GDR. You also highlighted in the exhibition at HKW that the activities of the artist networks you uncovered show equal density in Eastern Europe and Western Europe, as well as beyond, which, as you pointed out, counters the dominant narrative given of this period that Paris as the center of the art world was disappearing and New York was emerging in its place. How did local research in Hungary contribute to the project overall?

KK: Zsuzsa researched very specific materials that we ended up using in one video that is unearthing the relationship of Hungary to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) through cultural relations (administered by no longer existing state institutions in Hungary, such as the Solidarity Committee or the Institute of Cultural Relations) and exhibitions, as the Palestinian folk art exhibition that toured in European cities between 1978 and the early 1980s, including Budapest, at the Museum of Ethnography. All of these add to the thickening of the story. I think what is also nice about this iteration in Budapest is that there is a part in the exhibition—on solidarity actions in Hungary—where it is explicit that it is Zsuzsa’s work. Also, we were able to get access to the history and some of the works by Gyula Hincz who was the only participating artist from Hungary in the International Art Exhibition for Palestine in Beirut in 1978.

RS: We do rely on other people’s research, they are part of the thank you list, their research has fed ours.

ESz: A frequent question that emerges in relation to your project concerns the current status of the artworks that were part of the 1978 exhibition and the later collection. Was it clear from the beginning that your priority was not to restage the exhibition, nor to trace the artworks, nor to have original artworks in the exhibition?

RS: It was clear from the very beginning that we were only interested in understanding how an exhibition of this scale could happen, given the context. Also, for about the first two years, we were working with the assumption that the works were destroyed. When we met Claude Lazar, the French artist who was really involved in organizing the 1978 exhibition, we learned about the concept of the museum in exile, about the artist group Salon de la Jeune Peinture, and things really took a different turn. We were much more motivated to dig further in the research, and we became less and less interested in what happened to the artworks. Palestinian artist Nasser Soumi, who assisted in putting together the exhibition in Beirut in 1978, started an investigation on his own. He wrote a letter, a kind of testimony that he sent to his entire email list, and this document went viral. We also displayed it in the exhibition. This is the most significant proof that not all the artworks were destroyed.

ESz: One of the things that I find intriguing is that what you are doing within the research and the exhibition chapters also mirrors many of the methodologies of the original exhibition, in terms of it being itinerant, transnational, connecting networks, as well as the use of visual materials (posters, reproductions, and videos) as an important means of conveying a message.

KK: We want to imagine and design a lightweight exhibition than can travel easily, and hopefully to places where it might have particular relevance. It is definitely inspired from the content; it is precisely what this network was. Thus, bringing it back to these cities where the network was once active is important to us.

ESz: During the Free School, you also touched upon the precariousness of your research activity, that one of the reasons why it has taken a long time is that funding is scarce for independent research. What does independent research mean to you in terms of strategy?

RS: We are not academics, or at least we are not affiliated with an academic institution, and we do not have academic jobs. There are no state institutions that fund research that cannot be monetized, as in the end, a documentary and archival exhibition produces immaterial value and not material value. It could eventually bear an impact on the market, but it is rather a bridge too far. Basically, neither Past Disquiet nor Cartography of Artist Solidarity are exhibitions of contemporary art. If they were, then they could immediately be monetized. The outcome of this research is not very valuable to public institutions. We received support from private institutions and individuals who are involved in philanthropy, who are in tune with what is going on. This is mainly how we managed to find support. It was minimal, we also operated a lot on our own.

ESz: Many of the characteristics of the artists networks and actions in the 1960s-1970s you present in the exhibition also appear as a sort of desired future for the arts, especially in places currently undergoing major socio-political changes: political engagement and art plays a crucial role; it is for the people; it is networked, transnational, and grassroots, and even that cultural diplomacy takes art so seriously. What can we learn from these initiations for today’s situation?

RS: Probably one of the things that I love to underline the most is that this is an exhibition that reconstructs a world where militants cannot imagine change without artists, and artists are profoundly engaged with political change. I think this is one of the ways in which it is very relevant today. It is also an exhibition that recreates a world where artists had complete agency in constructing worlds for themselves, on their own terms, completely outside of the market.

KK: Which is hard to imagine today. I would say, I think for me, part of the hope is that these actions, which many people cannot imagine today, are very inspiring. People can be engaged and take a position in a physical space, not just on the Internet, make a stand, and produce objects and exhibitions that are meaningful, which may do or may not do something, but express their position. People are politically engaged today and stand by their position, but that takes very different forms. How present were these events to people at that time, that is a question to ask. It is also significant that so many of these works were in public space, not in a gallery or an institution. I think the use of public spaces in our part of the world is something that maybe does not happen as much today, our relationship to public space is different now.

RS: The state policies the public space, and for the most part, it has become privatized.

KK: Yes, it is less possible; you have to ask for permits to do things.

ESz: Similarly, in Hungarian the very notion of “publicness” or the public sphere (nyilvánosság)—the meaning of which is very much tied to the 1960s-1970s, to the subversive use of spaces in repressive contexts—is much more complex than to equate it with today’s notion of the public space. Talking about Hungary, Eastern Europe, and the 1960s-1970s, a questions that still surfaces, for instance to me, is how we conceptualize this region today: whether it is still relevant to understand it as a distinct entity, as the East of Europe, or it is now only a historical/academic question. In terms of geopolitics, how do you streamline your project to an international audience?

RS: I think the historical periods are relevant and are particularly meaningful when their residual traces are still active in the present: what you are living or what you are trying to unpack. Just like “former East” or “former West,” the notion of the “Arab world” is a geo-cultural construction. “North Africa,” “the Maghreb” are very different from what is called “the Levant” or “the Mashriq.” It’s very tricky when you say the “Middle East” or “Near East,” or the “Arab world.” The “Arab world” eludes the presence of non-Arabic minorities like the Kurds and the Armenians. All these constructions are potent, have a toxic effect, and need to be deconstructed. Yet, it does not mean that they are not meaningful, they still are.

KK: The exhibition starts with Palestine and in Beirut, but it ends up in more places than those two; it is not about the Arab world explicitly. What is interesting for both of us is precisely not to ghettoize things that way, but rather to think transnationally. That is what matters to us, and that is what drives our research.

ESz: Do you think that this kind of transnationality could be a model for today?

KK: I don’t think we are the only people trying to think that way. On the other hand, it is harder to work transnationally, as you have to have access or know different languages or people who speak different languages, possibility for travel, and I think that is what makes it harder.

RS: There has to be political will behind a desire to reconfigure the world under specific parameters such as transnationality. Globalization narrows the world, and a lot of scholars, curators, and artists resist this by foregrounding the transnational aspect of the making of things. The fabric of our life is profoundly transnational, whether we want it or not. Nobody comes from one race, nobody comes from one people, and no language has had a pure history. These are arguments against the new forms of fascism that comes with neoliberalism. I think this new transnationalism is our form of contemporary resistance.

________

Cartography of Artist Solidarity – Narratives and Ghosts from the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, 1978 is on view at tranzit.hu in July and August by appointment at office@tranzitinfo.hu

About the curators

Kristine Khouri is an independent researcher and writer based in Beirut. Her research focuses on the history of arts circulation and infrastructure in the Arab world. She curated The Founding Years (1969–1973): A Selection of Works from the Sultan Gallery Archives (2012) at the Sultan Gallery, and contributed as a writer to several publications, including Bidoun, Art Asia Pacific Almanac, and Global Art Forum 6.

Rasha Salti is a writer, researcher, and curator of art and film based in Beirut. She co-curated a number of film programs including The Road to Damascus with Richard Peña (2006) and Mapping Subjectivity: Experimentation in Arab Cinema from the 1960s until Now with Jytte Jensen (2010–2012), showcased at the MoMA, New York. In 2011, she was a co-curator of the 10th edition of the Sharjah Biennial for the Arts. Salti also edited a number of books including Beirut Bereft, The Architecture of the Forsaken and the Map of the Derelict (2009).

Together, Khouri and Salti are the founders of the History of Arab Modernities in the Visual Arts Study Group, a research platform around the social history of art in the Arab world. Their current work is focused on the history of the International Art Exhibition in Solidarity with Palestine that was opened in Beirut in 1978.

About the author

Eszter Szakács is a curator at tranzit.hu, Budapest, where, among others, she has been the curator-editor since 2012 of the ongoing collaborative research project Curatorial Dictionary. Previously she was a guest lecturer at the Art Theory and Curatorial Studies Department at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts (2013–2016) and an assistant curator at the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, Budapest (2008–2010). She is a co-editor of Mezosfera.

Notes

- For the background and the various chapters of tranzit.hu’s Parallel Chronologies project on exhibition histories in Eastern Europe in the Cold War, see the project’s website: http://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/ ↩

- Past Disquiet: Narratives and Ghosts of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, 1978, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, February 20 – June 1, 2015 and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, March 19 – May 9, 2016. Upcoming venues where the exhibition will be presented at include Stockholm, Beirut, and Santiago de Chile. ↩

- As Rasha Salti pointed out, organizing these cultural events was not only a question of “propaganda,” but they really emerged out of “invisibility,” or of a wide perception of the Palestinians as helpless victims (seeking the charity/compassion of the word) or terrorists. The Office of Unified Information was like a ministry of information or communication. Its mission was to communicate with its immediate constituency, i.e. Palestinians, communicate a representation (iconographic, narrative, and discursive/ideological), consolidate a sense of peoplehood, and mediate the cause to the rest of the world. ↩