This is a weird geography in which we live.

A geography that separates the world into those who define their own area and those who are confined to an area; those who can move freely and those who are immobilized by force; those who are acceptable and those who are unacceptable; those who are right and legal, and those who are wrong and illegalized; the superior and the inferior.

As I said, a weird geography.

Grada Kilomba

The first thematic issue of Mezosfera contributes to the on-going societal debates around migration and migration politics in Europe,1 introducing and examining related work by artists, activists, and thinkers from diverse cultural and geographical contexts.

It focuses on practitioners who have been engaged with migration politics on a longer term and whose work thus questions and contextualizes the contemporary rhetorics of “crisis.” They do not only represent, raise awareness, or comment on current debates, but also create tools in cross-sectoral collaborations at the intersection of art, political activism and human rights advocacy. They explore possibilities of structural and systemic change through radical imaginaries, propose new or other modes of knowledge production, and shift perspectives on hegemonic public discourses. Individual contributions to the thematic issue A Weird Geography range from diverse texts, films, and images to more unconventional formats, such as a refugees’ library, a migrant labor board game, and a conference report on human smuggling and escape aid. Both this selection and the present introduction advocate a post-socialist and decolonial approach, in the hope of complementing discourses from predominantly Eurocentric and Western (European) perspectives.

In the following, I reflect on recent political developments regarding the “refugee crisis”—a movement of people, whose management, control, relocation, etc. have been at the epicentre of EUropean politics and media attention since summer 2015—also addressing the isolated and partially externalized way in which this so-called crisis has been discussed and managed. I argue for its contextualization in other “movements” of contemporary migration, taking into account the impact of political, social, and economic inequality and injustice on a global, as well as a European scale, which clearly shows that migration politics cannot be reduced to asylum politics.

My personal connection to migration and related EUropean politics is (at least) two-fold: For the last three years, I have been living in Vienna, after deciding to leave Hungary for partly professional, partly economic-existential reasons. Here I got involved in a self-organized group called Precarity Office that brings together people from primarily EUropean countries (especially EUropean peripheries, PIGS and CEE2) around labor- and migration-related issues. In 2015, we organized a series of events on Mobility and Migration, discussing differences and similarities between the two terms used to discuss the movement of people in EUrope, as well as the rhetorics connected to them in public discourse and policy-making. In this text, I also draw on our collective discussions of migrant workers’ struggles at Precarity Office, stressing the importance of recognizing common struggles against growing precarity and the significance of connecting diverse experiences of migration.

During the “long summer of migration” in 2015, I was active as an independent volunteer at different border crossings and transit zones (Röszke, Hegyeshalom, Rigonce), and have supported friends seeking asylum, accompanying them through diverse legal and bureaucratic processes in Vienna. This engagement has given me an opportunity to meet many people on the move and to get better acquainted with their situations; this also informs the text.

Attempts to understand, reflect, and act upon current developments are often frustrated by the extremely accelerated speed with which changes—at the borders, in asylum legislation, policy-making, and public discourse—happen on both national and EUropean levels. This makes the situation of refugees and migrants even more precarious and also poses a challenge for political activists and supporters. In the following, taking a step back from the dizzying speed of day-to-day events, I focus on possible engagement on the longer term, exploring the scope of responsibility and agency we have in our own field of work, encompassing artistic, curatorial, and cultural practices.

Knock Knock. Who’s There?

Who Has the Right to Have Rights?

Instead of talking about a “refugee crisis” concerning the increase in migration to EUrope, I want to discuss the crisis of migration politics that includes not only irregular, or more precisely illegalized immigration, but also all other movements to and within EUrope that are allowed for within the current border and visa regimes. This is an important shift of perspective that resists isolating the situation of refugees and migrants entering Europe without the “right credentials to travel” and looks for connections between different migration flows: not to blend out differences, but to stress a complex and diversified approach that can offer other perspectives on contemporary migration as part of our everyday realities, as well as point to possible political alliances and solidarities between people on the move.

I see EUropean migration politics not only as a regulatory system that determines who to include and who to exclude, who can become mobile and who must remain immobile (as beautifully expressed in the above quote by Berlin-based Portugese author and artist Grada Kilomba), but also as a politics that translates our vision of EUropean society into pragmatic, legal, and bureaucratic measures. In this sense, I would like to connect the question of migration to that of citizenship, of rights and privileges determined by the nation-state we are members of. Although freedom of movement has been enshrined as a universal human right in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights since 1948, the attitudes of different states towards both the principle and practice of the freedom of movement remain highly ambiguous and politically charged. “The act of enjoying this right to travel is an ideological act which is predicated on a system of inequity”3—a reality clearly manifested in the current situation. The right to move (or the right to stay) is being intensively re-negotiated, not only due to increasingly restrictive asylum policies and constantly updated lists of “safe countries”—where the status of a country can change from one day to another (see the cases of Serbia and Turkey)—but also by other types of immigration legislation, such as the new UK policy to deport non-EU citizens, who earn less than 35.000 GBP a year, resulting in the unfair discrimination of low-wage, precarious workers.

“Europe Does Not Make Us Dream”

A Crisis of Citizenship?

How can citizenship and the granting of rights and privileges be re-considered: what kind of citizenship can we envision for societies of inclusion, rather than exclusion?

Reflecting on the notion of European citizenship, philosopher and feminist scholar Rosi Braidotti asks why nationalism is (still) capable of exciting us, while “Europe does not make us dream”?4 Why is the social imaginary on Europe so poor, and how is it possible to (re)awaken passions for a post-national European project? In advocating postnationalism (instead of transnationalism), she recovers the anti-fascist roots at the origin of the European Union and argues for a postnational European space in the anti-statal sense. Drawing on Paul Gilroy and Ulrich Preuss, she proposes flexible citizenships that entail participation on negotiable grounds and are not granted on the condition of being born somewhere, or being of the right color or religion: citizenships that are neither full-time, nor one hundred percent. She advocates nomadism as the only possible solution for Europeans, the only way to escape the pitfalls of nationalism: A nomadism that produces nomadic subjects5 in the sense of legal and political subjectivity, detaching citizenship from the sense of identity and the identitarian question.6

Reading Braidotti, it becomes clear to what degree our social imaginary is limited by current frameworks of modern citizenship and the nation-state. Many of us may falter when trying to imagine a citizenship that is not full-time, but flexible, while others who have more than one citizenship (as does Braidotti herself, holding Australian and Italian citizenships), will know exactly what kind of fragmentation and multiplicity she is talking about, when they think about being able to choose between passports, as a means of identification and self-representation at the borders they cross. While Braidotti’s proposal of a post-nationalist Europe seems particularly relevant with the current rise of nationalism and state racism in mind, she also points out that this proposal is rather utopian, if there is no political will at a European level to re-consider Europe as something other than the Europe of nations or the Europe of regions.

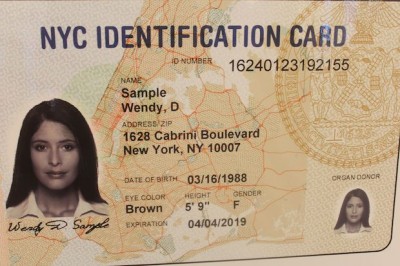

There are also other concepts of citizenship rooted in nomadism that propose change at a different level: the urban. English sociologist T.H. Marshall introduced his theory of urban citizenship in the 1950s, based on the straightforward idea that “everyone who lives in the same place should have the same rights.”7 In contemporary discourses, this concept has been advocated by Right to the City8 movements worldwide, seen as a possibility to move the citizenship debate from the nation-state to the city level, and thus grant rights based on the actual (physical) center of people’s lives. Urban citizenship meets immigrants’ rights in the case of sanctuary cities, a model adopted by several cities in the Unites States and Canada, that not only entitles residents to equal rights in the city, but also proactively protects immigrants’ rights (independently of their legal status) by enforcing strong anti-discrimination laws and preventing local administrations and police from cooperating with federal immigration authorities and from deporting local residents without valid immigration status. Urban citizenship is not widespread in EUrope. However, recent grassroots campaigns to adopt concrete measures, as well as a European model of sanctuary cities called refuge cities argue for its potential as a possible response to the democratic deficit of growing migrant populations living and working in European cities, who are not granted equal social rights and access to participation in political life.9

“On the Prison of the Possible” 10

Disengaging from the Nation-State

Conceptualizing citizenship on an urban or on a post-national (in Braidotti’s case, European) level challenges the current institution of citizenship regulated by the nation-state and points out the possibility of change at non-state levels. Recent “city to city collaboration” between Barcelona, Lampedusa, and Lesbos concerning the relocation of refugees and providing mutual support, highlights the potential of cities to act as autonomous actors in the European political arena, and hopefully serves as a precedent for more intensive collaboration between municipal governments and transnational, as well as local solidarity movements in the future.11

But what about agency on the individual level, what personal political agency do we have in terms of citizenship and nationality? What right do we have to self-determination?

In her work Stateless By Choice. On the Prison of the Possible, featured in this thematic issue, Núria Güell aims to disrupt the status quo and attempts to renounce her nationality and thereby citizenship by “appealing to the state to become stateless” (see the resignation letter and our interview with the artist). Her approach is a radical critique of our efforts to ensure more equality by giving more rights to do those who have less. Rather, she focuses on the source of our privileges, such as nationality/citizenship, and tries to dismantle the legal frameworks that produce this differentiation.

She mobilizes our political imaginaries to challenge the relatively new institution of the nation-state (a 19th-century European phenomenon) that has achieved global hegemony due to the recognition of the former colonies’ sovereignty and right to self-determination with the stipulation “to establish a unit of collectivity that demands to be acknowledged as a state or nation”—leaving no other option than the proliferation of nation-states. By attempting to break the social contract with the state, Núria Güell advocates post-state self-organization and post-identity politics that create new social contracts and new forms of belonging and community. She strives to exercise her right to self-determination that is not unrelated to the personal political agency that I find inherent to the act of migration.

Land of Opportunity

Migrant Workers’ Struggles from Post-Socialist and Post-Soviet Perspectives

Can we consider migration as a manifestation of personal political agency—especially when talking about irregular or more precisely, illegalized migration, the movement of people who do not enjoy the privileges of legal mobility? In the current political debates and media coverage of the “refugee crisis“12 in Europe, there is a prevailing discourse on deservingness that differentiates between forced and voluntary displacement, between refugees and economic migrants. The categories of “good” and “bad” refugees are thus created, based on the assumption that some people risk their lives coming to Europe to abuse the benefits of asylum. This discourse stresses moral duty towards refugees and stigmatizes economic migrants, not only ignoring the realities of structural violence and post-colonial economic inequalities that push people to migrate in order to survive, but also the fact that becoming a refugee is practically the only way to legally enter the European Union with the current migration policies in place.13 The problematic aspects of such a moralizing approach are brilliantly analyzed in a recent article published in American Ethnologist. I would like to take this line of thought a bit futher and expand its scope beyond current events to re-consider migration as a micro-strategy used to combat social, political, and economic inequality through displacement, a means of re-distributing wealth and accessing political and social rights bottom-up, in resistance to top-down politics that determine “who has the right to have rights,” but fail to address social justice on a global scale.

Can we understand migration across countries as a social movement for equal rights and opportunities? And if yes, what alliances and solidarities does this entail between different social and migrant groups? Where and when do these struggles end?

Two contributions to this issue focus on migrant workers’ struggles from post-socialist and post-Soviet perspectives. On the one hand, they explore the common grounds between migration to EUrope and inter-EUropean migration—from the so-called peripheries to the centres of economic power and growth—in the context of struggles against precarity. On the other hand, they try to expand our tendentially Eurocentric approach by looking at migration to Russia from the former Soviet Central Asian republics. Both contributions highlight migration flows that respond to pervasive trends of social, economic, and political inequality—of income, opportunities, education, and professional development, as well as rights—within the EU and the former Soviet Union. They both stress that inequality is also reproduced—legally and socially—through migration; that is, in the host societies via processes of marginalization, precarization, and institutionalized racism.

Bogdan Droma describes his involvement in the construction work of the Mall of Berlin and in the ensuing protest movement, Mall of Shame, after their wages were not paid. In an interview—first published in the Romanian Gazeta de Arta Politica (Gazette of Political Art) and re-published here with an introduction by Ovidiu Pop, co-editior of G.A.P.—he shares his views on the motives driving migration from Eastern European countries to Western Europe. He reflects on the collapse of the stereotypical (self-)representation of the West as more correct and less corrupt in terms of labor rights, while exposing mechanisms of exploitation and discrimination.

Artist Olga Zhitlina and human rights advocate Andrei Yazimov have co-authored the project Russia, Land of Opportunity to address diverse forms of precarity experienced by migrant workers in Russia. They created a migrant labor board game as a tool for sharing knowledge—legal and bureaucratic information, as well as advice—with affected foreign workers, while making accessible their experiences—the risks and opportunities at stake in labor migration—to majority society in Russia, with the aim of fostering solidarity and understanding towards the often marginalized migrant populations. The game plays with strategies of immersion and identification as a form of knowledge production. It is at the same time a historical document and a point of departure to initate discussions on necessary policy changes in labor and migration law in the Russian Federation.

Both the protests of the Mall of Shame and the scenarios that are played out in Russia, Land of Opportunity point to the challenges of bringing narratives of displacement and exploitation into the public discourse, while resisting victimization and (re-)claiming political subjectivity.

Smuggling Subjects

Solidarity and Its Discontents

In her video While I Write (2015) Grada Kilomba precisely and sensitively mediates the intellectual and emotional work involved in self-empowerment, in speaking “up” from a marginalized, oppressed, or silenced position, as well as the fear and anxieties of being examined and perhaps invalidated.

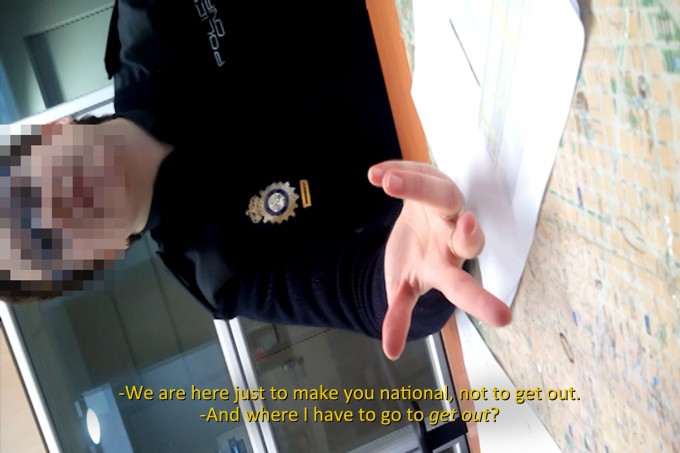

Her observations on becoming “the author, and the authority on my own history” strike me as particularly relevant, when encountering the Refugees’ Library initiated by the artist and activist Marina Naprushkina, also featured in this thematic issue. The volumes of this library are illustrated records of court trials, documenting the hearings of people seeking asylum in Germany. Meant to encourage discussion about German and European asylum and migration policies, they are not only archives of different aslyum cases made available to the public, they also trace and expose the power relations, hierarchies, and eventually the violence of examination and possible invalidation inherent to the interactions between the asylum-seeker and the authorities. Instructive for both majority society and refugees, the archives are also meant to be used as learning tools in preparation for asylum interviews and appeals.

The vertical politics that plays out on a micro-scale on the pages of the Refugees’ Library locates agency and action necessarily and exhaustively on the side of the state and leaves no room for agentive responses by migrants.14 The state assumes the position of absolute responsibility and authority vis-à-vis people on the move (granting asylum, providing accommodation, social help, etc.), but does so without granting neither the possibility, nor the right to negotiate, actively influence, or perhaps even co-design the terms on which this authority and responsibility is exercised, by withholding basic rights (e.g. the right to work) that could lead to an increase in agency on an individual, as well as a collective level. Similar hierarchies are reflected in the humanitarian approach to refugees and migrants that the Argentinian anthropologist and philosopher Miguel Mellino calls humanitarian reason or management: this substitutes the politics of rights and justice with an ethics of compassion and suffering. He criticizes certain NGOs that provide humanitarian aid on a global scale for operating in a complementary way to the ”international order” and hence contributing to the reproduction of the above mentioned vertical politics of domination and control, and thus framing people on the move as passive victims in what he calls the “ethical imperialism“ of “I will save you.“15

The essence of Mellino’s critique is articulated in the subversive logo of Fluchthilfe & Du (Border Crossing & You), a Vienna-based activist initative that criticizes the EU border regime and its migration policies. The logo appropriates the campaign Caritas & You of Caritas, a charity organization active worldwide, that appeals to the compassion of those privileged enough to help to collect donations to support the victims of suffering. But who can afford solidarity if assistance to refugees is limited to acts of charity? This is exactly the moment in which the ”refugee” is produced as a non-subject who waits for the cure or guardianship of someone, to be able to reach the status of subject—accentuating the logic of victimization and marginalization—while undermining precisely the personal political agency inherent to migration.

While Caritas distances itself from “human smugglers,” that is, people whose assistance to refugees made it possible for them to come to Austria and apply for asylum in the first place, Border Crossing & You takes a less hypocritical approach and envisions border crossing as a paid service, publicly soliciting support for the refugees’ struggle for freedom of movement and calling for active escape aid.

Another contribution to this issue is an overview of the International Smugglers’ and Trafficking Conference, co-organized by Border Crossing & You that endeavored to debunk the contemporary myth of “criminal smugglers” by examining the historical tradition of escape aid and human smuggling, especially during the times of WW II and the GDR. As an event dedicated to discourse production and knowledge exchange, it offered a differentiated view of smuggling, including questions of renumeration, raising awareness of the fact that criminalization tends to affect vulnerable social groups (fellow refugees, other migrants or minorities in precarious situations) for whom smuggling may be the only source of livelihood. Conference participants stressed that the most important is that “the smugglers do their job“—whether or not money is involved is not the main issue. It is crucial to note the differences between the social situations of people providing escape aid: better off, middle class activists and helpers may be able to offer their services for free and organize refugee convoys using their symbolic and financial capital, but not everyone can afford to do this. Mimicking an annual trade event and provocatively advocating professionalization rather than illegalization, the conference’s agenda includes the re-branding and re-evaluation of human smuggling and trafficking in the service sector.

Unwanted Entities

Deportation As the Order of the Day

It is alarming to see to what degree deportation seems to have become the order of the day and how it affects diverse vulnerable migrant groups and their “right to stay” in EUrope: those whose asylum applications have been rejected; those affected by the new immigration legislation in the UK that foresees the deportation of non-EU citizens whose earnings are too low; and most importantly, all the refugees and migrants currently arriving to Greece from Turkey. Deportation has become a household term, regularly used in public discourse for migration and population management: it actively disposes of “unwanted entities,” and reinforces the repressive control that is constitutive of the neoliberal technology of government.

Two contributions to A Weird Geography address the institutionalized practices of forced deportation: I Ain’t Gettin’ on No Plane! How to Stop a Deportation is the simulation of a deportation on a passenger airplane, with “safety instructions” on how to prevent the deportation and take solidary action. The other film made by the human rights organization augenauf (open your eyes) shows the process of a forced deportation by Swiss authorities, reconstructed on the basis of numerous interviews with people affected, as well as the training material of the Swiss police. The documentary was made after a young man from Nigeria, Joseph Chiakwa, died in 2010 at the Zürich airport, while being subjected to this treatment. Notably, both films raised a great deal of attention and controversy in their respective countries, Austria and Switzerland: How to Stop a Deportation is currently being prosecuted for promoting the breach of law by the right-wing Freedom Party of Austria—the process was launched recently, almost two years after its making and release. The reconstruction of augenauf was banned from Swiss television and is currently only available on YouTube.

I find both developments revealing in terms of what capacity we have to dis-identify with the civilizing myth of EUrope, and to confront the widespread assumption—still insisted on and maintained in today’s critical political and humanitarian situation—that “Europe is a place of rights, of integration, a place of community, of cosmopolitanism”—as Miguel Mellino underlines in his sharp critique of European humanism.16

A Weird Geography wishes to raise the question of how to build on this disenchantment and disappointment. How can we use the critique of humanitarian reason and vertical politics to re-examine our own positions within possible political alliances and emerging solidarities, across diverse experiences of migration and precarity? Contributions to this issue insist on resisting the idea of “limited good” advocated by Europe-wide neoliberal austerity policies and instrumentalized to provoke de-solidarizing between vulnerable social groups. Instead, they aim to reframe the migratory experience as a source of knowledge production and political subjectivity, resulting from the constant re-positioning and situating of ourselves entailed by displacement.17 They stress the need for joint efforts to re-visit and strategically use the privileges we might hold (especially addressing EU citizen readers) in the fight for equal rights and opportunities that include a freedom of movement that is not only legitimated by necessity—precisely as it is a freedom—and is accessible to all.

About the author

Katalin Erdődi is an independent curator and cultural worker in the fields of contemporary art and performance. Her practice focuses on cross-disciplinary collaboration, politically engaged artistic and curatorial strategies, and art in public space, understood in the broadest sense as social, architectural, and discursive space. Central to her work is experimentation with different formats, from performance through exhibition-making to site-specific and process-oriented projects, with an interest in art as social practice and a tool for knowledge production.

She has co-founded and co-curated PLACCC Festival with Fanni Nánay (2008–2011) and has worked as a curator/programmer for a number of leading art institutions, such as brut/imagetanz festival (Vienna), Museum of Contemporary Art (Leipzig), Ludwig Museum (Budapest), and Trafó House of Contemporary Arts (Budapest).

Alongside her curatorial work, she is involved in the activities of various self-organized political groups in Budapest and Vienna, where she lives and works.

Notes:

- I use EUrope/an whenever referring to the European Union to differentiate between the EU and Europe as a geographic entity. ↩

- PIGS: Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain; CEE: Central and Eastern Europe. ↩

- Freya Higgins-Desbiolles. “Hostile meeting grounds: encounters with the wretched of the earth and the tourist through tourism and terrorism in the 21st century.” In P. M. Burns & M. Novelli Eds. Tourism and politics: global frame-works and local realities. Kidlington, Oxon: Elsevier: 309–332. ↩

- Rutvica Andrijašević. “Europe does not make us dream. An interview with Rosi Braidotti.” (2002) ↩

- Rosi Braidotti. “Nuovi soggetti nomadi. Transizioni e identità postnazionaliste.” Rome: Luca Sossella Editore (2002). As Rutvica Andrijašević explains: “In this volume, published only in Italian, Braidotti returns to the reflection on the nomadic subject already begun in her famous Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994). The new book re-edits the four initial chapters of the earlier text, to which it adds a new chapter, entitled “Gender, identity, and multiculturalism in Europe”, where, facing the agonic Europe of critical thought, one enters a conception of Europe as the space of this nomadic subject that is periphery, margin, difference, and plurality.” Rutvica Andrijašević (2002). ↩

- Andrijašević (2002). ↩

- Henrik Lebuhn.“Urban citizenship, border practices and immigrants’ rights in Europe: ambivalences of a cosmopolitan project.” Open Citizenship 4.2 (2013). ↩

- David Harvey. “The Right to the City.” New Left Review 53 (2008). ↩

- Recent efforts to concretize and realize urban citizenship in Europe include: the art space Shedhalle’s long-term, cross-sectoral collaboration The Whole World in Zürich advocating “cities, not states” and proposing “concrete interventions into the Swiss migration politics”; the new policy of the city of Barcelona: Barcelona, Refuge City; the debate Wien für alle! Bewegungen und Perspektiven für eine Stadt der Solidaritda (Vienna for All! Movements and Perspectives of a Solidary City) with local, as well as Swiss, German and Canadian initiatives. ↩

- Quote from the title of Núria Güell’s eponymous work: Stateless By Choice. On the Prison of the Possible. ↩

- Manuela Zechner, Bue Rübner Hansen. “More than a welcome: the power of cities.” ↩

- I see the term “refugee crisis” itself as a highly problematic construct in public discourse, as it seems to imply that the crisis is inherently linked with the refugees, suggesting them as the source of the “problems.” ↩

- Seth M. Holmes, Heide Castaneda. “Representing the ‘refugee crisis’ in Germany and beyond. Deservingness and difference, life and death.” American Ethnologist43.1 (2016): 1–13. ↩

- Annastiina Kallius, Daniel Monterescu, Prem Kumar Rajaram. “Immobilizing mobility: Border ethnography, illiberal democracy, and the politics of the ‘refugee crisis’ in Hungary.” American Ethnologist43.1 (2016): 25–37. ↩

- “Crisis of humanism, critique of humanitarian reason. A conversation with Miguel Mellino.” The interview was conducted on the radio show Clinamen in Buenos Aires on September 8, 2015. Edited by Kelly Mulvaney and Niki Kubaczek, transversal texts. Translated by Kelly Mulvaney. ↩

- Miguel Mellino (2015). ↩

- See more on this line of thought at Situating Oneself: Politics and tactics within displacement. An international laboratory exploring the embodied politics of relating across places, contexts and social spheres. With Manuela Zechner, Marcelo Expósito, Paula Cobo-Guevara, Claire English, Marc Herbst, Esquizo Barcelona Group, and Bue Rübner Hansen. Hosted by La Electrodoméstica. ↩