Reading the inspiring essays of issue #2 made me further reflect on what has been a longstanding preoccupation of mine, namely, the relationship between the arts/cultural production and the state, or, more specifically, between the mezosfera and the state.1 It seems to me that the question of how to dis/engage the state (and how to theorize this dis/engagement) is a crucial one for the cultural producers inhabiting the mesosphere. I will immediately lay bare my own stand: disengagement can only be a tactical one, a move within a complex war of position, and no long-term option. Together with Vlad Morariu, I believe that we need to question an antagonistic politics of principled non-involvement along with what Michael Foucault called “state phobia,” that view of the state as embodiment of all evil and major hindrance to societal development that is rampant these days, brought upon by neoliberal hegemony, while also common among the radical left.2 With Morariu, I believe that the task is to “think of tactics and strategies of getting involved and reoccupying the very structures of the system that have been abandoned.” This does not mean to abandon “independence” and the mesosphere altogether, but quite the contrary, for independence should be a matter of constantly renegotiating boundaries that are always already blurred and shifting.

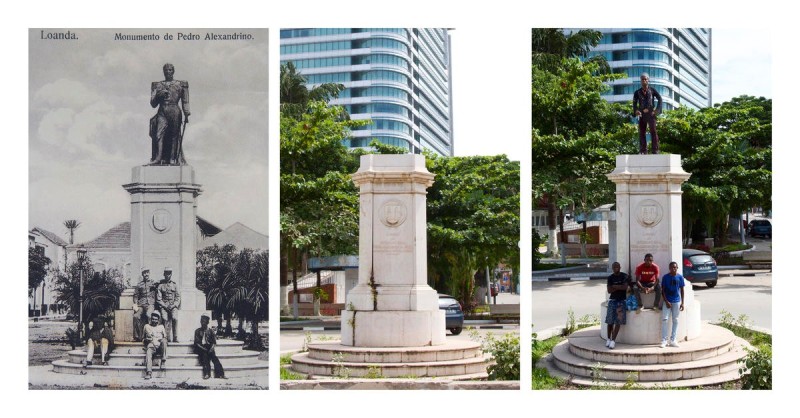

Courtesy of the artist and Beirut Art Center. Thanks to Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg. Its first version shown in 2005, The Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind mimics the traditional form of the national museum, with its artefacts displayed in cabinets. This installation does not simply enact the Palestinian desire for statehood and its attendant institutions, while at the same time critiquing it; in fact, it has staged the very first Palestinian national museum.

The starting point of my reflection is that things, in general, get much worse for the arts and culture when the state is rolled back, as neoliberals preach. Usually the justification of this kind of policymaking is that the state is not only authoritarian but also burdensome and inefficient, while others, like the private sector or civil society, get the job done and are, by nature, more democratic in the ways in which they stimulate and make visible a variety of different views—or so goes the neoliberal vulgate. But the recent, drastic cuts in state funding for culture that have been implemented in most European countries in a policy move away from dirigiste models have had dramatic effects across the spectrum, and have probably meant less and not more freedom for artists and cultural producers. Italy, for example, has seen the ministry of culture’s budget halved between 2000 and 2013, a development that has brought widespread privatization and loss of access to culture for many of the country’s citizens.3 Bluntly put, disabling the state’s role in culture delivers artists and cultural producers to something (often) worse, namely, the whims of the market, with its built-in asymmetries and opacities and its specific logic of selection. This of course does not mean that all forms of state interventions (or all forms of state engagement) are to be valued.

My second starting point is the crucial insight offered by Foucauldian political analyses that the state is no autonomous entity clearly separated from (civil) society.4 The very boundaries of the state are elusive, porous, shifting—ultimately because they are the very object of multiple contestations and power struggles.5 This is particularly the case with advanced liberal democracies. For Foucauldian thinkers, this form of government works through a multiplicity of governmental technologies extending well beyond the alleged confines of the state,6 and knowledge and culture play a very important role in it. Think, for example, of NGOs and public-private assemblages carrying out former state functions or policymaking’s incessant invocation of the creative sector to solve all sorts of socio-economic problems, from urban regeneration to local de-development and social exclusion. More and more theorists understand the state as “an emergent, partial, and unstable system that is interdependent with other systems in a complex social order.”7 This does not mean that the state does not reproduce domination or that it is a just one. Rather, it means that “producing and maintaining the distinction between the state and society is itself a mechanism that generates resources of power.”8 Policing the boundaries of the state, negotiating what is in and what is out, is the locus of important power struggles. And the struggle over the very boundaries of the state, I want to suggest, is key to those who inhabit the mesosphere. In turn, this is not a clearly defined layer but rather a “zone of engagement,” a playing field or even a battlefield, whereby establishing the frontline in a certain position and along a certain route is one of the main stakes.

What is the meaning of “independence” within this unstable, tense zone? What I suggest we steer away from is an understanding of the mesosphere as a novel term for a romanticized view of civil society, as a creative, self-fulfilling life-world fully independent from and in fact providing a radical alternative to the state as an embodiment of evil. At the same time, one should not throw the baby out with the bathwater, for the mesosphere does indeed provide for a fundamental space of innovation and contestation of the state’s authoritarian and exclusionary tendencies. Yet, the promise of such aesthetic and socio-political criticality (the unacademia of Jan Sowa, the Living Memorial discussed by Lóránt Bódi) lies also, from a sociological viewpoint, in its future-oriented experimental institutionalism, and its potential import on “real” institution-building. A different, though equally interesting question, we might ask ourselves is to what extent the modern territorial state provides the necessary condition for the mesosphere to exist. In short, I argue for a reading of independence as the name of a paradox, the name of a distance and the very impossibility of it. For Jan Sowa, distance from formal institutions is the cypher of contemporary knowledge-generating practices that oppose the sterile, ossified knowledge production taking place in an academia subdued by both state and capital. Building on his insights, while politely disagreeing with him, such distance is to me the name of a relation, of a productive tension, since 1) critical knowledge production takes place within the academy too, and the latter does still offer (at least to some, i.e., those on permanent contracts) space for a freedom of inquiry often threatened elsewhere by conditions of precarity and dependence on targeted, goals-oriented, and short-term project funding and a cannibalistic commodification of knowledge and culture; and 2) we should aim to bring more “unacademia” or what Ana Vujanović calls “walking theory,” affective, organic, knowledge, or knowledge that dances, within the academy itself.

A good example of such practices of independence or engagement-at-a-shifting-distance is the Teatro Valle experiment, a theater and former opera house in Rome that a group of artists, cultural producers, and concerned citizens occupied in 2011. Under threat of an impending privatization following major cuts in the Italian state cultural budget, this theater became a center of cultural and political experimentation allied with a broader movement for the commons. Over the years, the Valle experiment has had both legal implications—becoming the first legally recognized foundation for the commons in Italy—and was taken up by the local municipality as a model of decentralized urban governance.9 The relationship with the municipality was the object of heated debates among Teatro Valle people, and particularly between those who saw it as a form of cooptation and those who instead viewed it as an empowerment of the movement, its turning into a constituent power shaping the world of formal institutions of the state.

The current stance of Hungary’s mesosphere is one of disengagement from an increasingly authoritarian state, with artists and cultural producers fighting to carve out for themselves a free space from an encroaching government and an expanding state; but it is likely that the people making up Budapest’s Living Memorial may well have to ask themselves similar questions soon. How to engage state institutions of memory and shape their narrative (to maximize social import) without being coopted or instrumentalized by them and the local state? How to activate from the threshold, so to speak, a process that I’d call, following Nora Sternfeld, “institutional unlearning” and learning again? In other words, what can propel institutions to “unlearn” their past, the burden of entrenched patterns and dispositions, and overcome institutional inertia to reform? And how to maintain critical distance while negotiating institutional thresholds?

The most interesting example of practice at the threshold of the “state” that I have encountered, paradoxically, is the work of Palestinian artists and cultural producers who have played with the format of the national museum and other “ideological state apparatuses”10 in order to realize them in spite of Palestine’s statelessness and ongoing occupied condition. What began as art projects has resulted in the establishment of a number of national cultural institutions, including several museums but also the Art Academy, that are, at present, the only functioning ones in their domain. They are half art projects, half real institutions. Also begun as art project, the International Academy of Art, Palestine, for instance, quickly became the first and only contemporary art program in Palestine. It went through very long negotiations with the Palestinian Authority, the non-sovereign quasi-state entity administering (parts of) the West Bank, and strongly resisted certification by the Ministry of Education, due to Academy members’ fears of bureaucratization and the loss of their alternative, anti-institutional ethos—but this caused major problems for students in getting their degrees, and ultimately threatened the endeavor as a whole. Now, the Academy will become an official faculty of Birzeit University, the main Palestinian institution of higher knowledge. While contributing to state-building, the artists and teachers of the new arts faculty will surely have to face a number of complex if productive tensions and negotiations.

In the context of cognitive-cultural capitalism, policy-making has instrumentalized and “governmentalized” culture and the arts (together with civil society) to solve a number of social problems and to stimulate economic development and urban regeneration.11 In turn, social practice art has reacted to the dissolution or disassemblage of older institutions of the state by launching a kind of experimental institutionalism, informal, creative statecraft at the threshold of the state, like the case of the Teatro Valle shows. Is this a threat—the final dissolution of art’s autonomy and the triumph of commodification—or does it simultaneously entail a potential, the possibility of seizing new terrains and of negotiating new, promising boundaries between the world of formal institutions and the mesosphere? The answer to this question is always specific to particular locales and particular moments in time, contingent on the specific assemblages of socio-political forces and sedimented institutional histories that make these locales unique. At times, tactic disengagement, is the right answer. In the battlefield of the mesosphere, however, it is perhaps advisable to steer away from state phobia and to relate to the “state” and its institutions as Nikita Dhawan’s suggests,12 namely, not as monsters but as pharmakon, both poison and counterpoison, or medicine: the challenge being to transform the former into the latter through sustained critical dis/engagement.

A contribution to issue #3 Back to Basics. Responses to the Issue Inside the Mezosfera.

About the author:

Chiara De Cesari is a cultural anthropologist and Assistant Professor with a double appointment in European Studies and Cultural Studies at the University of Amsterdam. She has published articles in numerous journals including American Anthropologist, Memory Studies, and Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism. She is currently finishing a book titled Heritage and the Struggle for Palestine, under contract with Stanford University Press, and is co-editor of Transnational Memories: Circulation, Articulation, Scales (with Ann Rigney). Her research focuses on memory, heritage, and broader cultural politics as well as the ways in which these change under conditions of globalization, particularly the intersection of cultural memory, transnationalism, and current transformations of the nation-state. She is also interested in the globalization of contemporary art and related forms of creative institutionalism and statecraft.

Notes

- For example, Chiara De Cesari, “Anticipatory Representation: Building the Palestinian Nation(-State) through Artistic Performance,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 12/1 (2012): 82-100 or Chiara De Cesari, “Creative Heritage: Palestinian Heritage NGOs and Defiant Arts of Government,” American Anthropologist 112/4 (2010) : 625-637; see also Chiara De Cesari, “Heritage beyond the State? Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics in Post-neoliberal Times,” forthcoming, and Chiara De Cesari, Heritage and the Struggle for Palestine, forthcoming, under contract with Stanford University Press ↩

- Mitchell Dean and Kaspar Villadsen, State Phobia and Civil Society: The Political Legacy of Michel Foucault (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016). ↩

- Mitchell Dean and Kaspar Villadsen, State Phobia and Civil Society: The Political Legacy of Michel Foucault (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016). ↩

- E.g., Akhil Gupta and Aradhana Sharma, “Globalization and Postcolonial States,” Current Anthropology 47/2 (2006): 277–307. ↩

- Timothy Mitchell, “The Limits of the State: Beyond Statist Approaches and Their Critics,” American Political Science Review 85/1 (1991): 77–96. ↩

- E.g., Peter Miller and Nikolas Rose, Governing the Present: Administering Economic, Social and Personal Life (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008); see also Michel Foucault, “Governmentality,” in The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, edited by G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991). ↩

- Jessop, Bob. “The State and State-Building,” Oxford Handbooks Online. 23 Jan. 2017.http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199548460.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199548460-e-7. ↩

- Mitchell, “The Limits of the State,” 90. ↩

- See Ugo Mattei, “Institutionalizing the Commons: An Italian Primer,” in Global activism: art and conflict in the 21st century, edited by P. Weibel (Karlsruhe, Germany: ZKM, Center for Art and Media, 2015). ↩

- Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. (London: New Left Books, 1971) ↩

- George Yúdice, The Expediency of Culture: Uses of Culture in the Global Era (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003); Dave O’Brien, Cultural Policy: Management, Value and Modernity in the Creative Industries (London: Routledge, 2014). ↩

- Nikita Dhawan, “The Unbearable Slowness of Change: Protest Politics and the Erotics of Resistance,” in The Philosophical Salon: Speculations, Reflections, Interventions, edited by Michael Marder and Patricia Vieira (London: Open Humanities Press, 2017), 30–33; see also Nikita Dhawan, “Postkoloniale Gouvernementalität und ‘die Politik der Vergewaltigung’: Gewalt, Verletzlichkeit und der Staat,” Femina Politica 22/2 (2013): 85–104. ↩