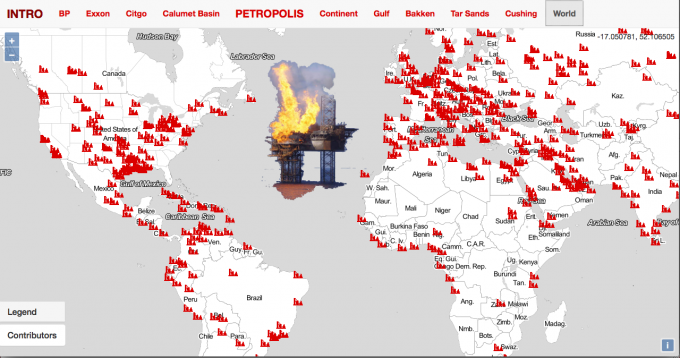

On the occasion of a lecture and a workshop organized by the Translocal Institute in Budapest, art and cultural critic Brian Holmes talked about the importance of realizing how in the current geological epoch, in the Anthropocene, human generated energies “overwhelm the forces of nature.”1 He urges people to act collectively for social change, in order to avoid the predictable future of ecological and social disasters. As a working example, Holmes has developed an online map-based archive “Petropolis,” pointing at the devastating processes of oil industry in the Chicago metropolitan area and its connection to the global petroleum complex. The project also underlines how local actions can have global effects, and how change can be triggered collectively.

Tünde Mariann Varga: For me, the ideas of your recent texts2 show a complex way of how art and activism can mutually reinforce each other. This complexity is manifest in the map you produced on Chicago’s petrol based industrial areas, which also seems to promote an evolving network of ideas that could help people to be aware of the origins of their local problems (in this case, the damages of the oil industry) and be more active in standing up for themselves against profit-based interests with often devastating outcomes. Can you tell me about the map and the reasons for creating it?

Brian Holmes: I began to make an extensive map of the petroleum economy in the Chicago metropolitan area. I started it because there were social movements in Chicago fighting against a petroleum waste product called “petcoke” that had become a real problem for people living in the neighborhoods near the refinery. I have always been active in such movements, and as an intellectual, I try to make something useful in activist terms. So, I designed the map to give people information about their own city, but also about the current political economy. The local problem is part of a much larger one, namely our dependency on the increasingly intensive use of oil, which is ultimately an ecological death threat, it’s actually suicidal. I wanted to show the full scale of the extractive economy and the corporate power it creates. In particular, this map shows how our daily lives in Chicago are connected to the tar sands oil extraction region of Canada, which is often called the most environmentally destructive project on earth. The map is a way to bring awareness to the people about where that oil comes from, and what kind of economy it is connected to.

VTM: Your map starts from a local project and gets people to understand that locality in a much wider context. You believe that you as an intellectual can help people to understand their situation and the causes of their problems by sharing a wider knowledge. What is your aim, and how do you make or manage such a vast project?

BH: Eszter Szakács, one of the participants of the seminar at Translocal, asked me who made the map, and my first answer was, well, I did. She was surprised because she thought there was an institution behind it! But the truth is that I could never have done that all alone, so I took some time to explain that. For one thing, the map, like all of my work, is made with open source software, so at the very basis of its making, there is a collective creation, with software that is free to use, and which you can also contribute to. If you know how to program or if you work with people who do, you can actually help make the software into a more effective tool, and it will still remain free. Then I used various kinds of files that come from public information sources, which might be universities or agencies of the state. I don’t think all aspects of the state are necessarily evil; after all, there is a tradition in western society of public knowledge that has to do with science and educational systems, what we call common goods. There is a lot of talk in social theory now about the common, and about the commons as a socio-economic reality in European history, referring to the co-management of pasture lands that didn’t belong to any individual but could be used and cared for by all. Today, knowledge commons are very abundant, there are lots of them, free software is a case in point. I also have many collaborators who have generously added different contents to this map, making their own knowledge common. Nobody could do something so complex all alone.

TMV: There is a lot of networking knowledge in it, and these people work voluntarily, and their labor contributes to the common good, which is also the opposite of what neoliberal capitalism does by turning labor into capital.

BH: Yes, that is very much the case. But the map combines the efforts of people who work voluntarily, who give their labor freely, and of people who work for institutions that are oriented towards the common good. I think you have to take both of these dimensions in account. Institutions are often problematic, but one has to try to figure out what their strengths are. A lot of very valuable work is done in institutions, and it can reinforce other kinds of more spontaneous grassroots efforts. At best, it can create a virtuous circle, where you have two different dynamics that reinforce each other.

TMV: You also mentioned that to reach your aim it is a good form to organize a carnival like protest, when so many people go to the streets that the police cannot do anything, because they cannot put everybody in jail. What do you see the importance of protest is?

BH: Protest is fundamental to democracy in a neoliberal society where changes happen really fast, and the power of the corporate state is really overwhelming. Democracy rests on formal institutions plus civil society, and protest is a necessary form of expression whenever the formal institutions do not produce democratic results. However, the way it works in a democracy is that protest points a finger at dysfunctions, at injustices, inequalities, corruption, and also at structural problems. But then the pointing finger has to lead to changes at other levels, otherwise it has been in vain. Self-organization at the grassroots has the very positive result of promoting collaboration, communication, and expression that extends beyond the initial group that has started the protest movement and becomes more general in society. That can create a popular cultural transformation.

This aspect of transforming protest into durable results is complex, and today, I think that there is a reason to mobilize people for longer term issues, because the challenges of society today are middle or long term, and we are not very well equipped to face them. So, there are also issues that go beyond the capacity of immediate protest. The relation between intellectuals and other segments of society is to provide some kind of a steering force to orient society to give it other stars in the sky, not just dollar signs.

TMV: Do you think intellectuals can take the role of making people aware how they can overcome their problems that derive from social or political inequality?

BH: We have major challenges on a number of levels. The structure of public institutions under neoliberalism has directed every person to work towards business solutions: you have an expansion of the corporate way of doing things. Intellectuals have largely gone along with that, they’ve accepted to become profit seekers on a high performance market of publishing, conference circuits, universities, exhibitions, and media. It results in a generalized competition where everyone acts against everyone else, rather than trying to contribute to elements that would enrich a public debate.

The role of intellectuals in a social movement is to help shape political orientations. First by taking a stand that large numbers of people already have taken, and then giving that position a more definite form and returning it to the people concerned, so they can decide what to think about it now, how much it reflects what they have already done, and what they want to achieve in the future. This is the case with the map, for example. And I don’t think one should refuse that role. It does not mean you are leading people, or trying to manipulate them. It means you are contributing to something that is larger than you and is not in any single person’s hand, because each contribution is debated, re-oriented, it might be used for another purpose. That’s the most rewarding thing for me.

TMV: You also say that aesthetics is a symbolic system that could change people’s way of thinking. Would it be the point where sensuality and aesthetics come into the picture? How would that work?

BH: What is important is how we orient ourselves, how we understand what we should do in life. One of the ways we understand ourselves is through the kinds of figures we create, which allow us to imagine our position with respect to other people. Those figures as they present themselves to us at first are wordless, they are the figures of the imaginary order, the symbolic order. This is a realm that has real effects on society. Artists are not the only people who do it, but art is interesting when it connects to people’s activity in society. That’s is why activist artists are important. It’s no accident that artists tend to be voracious readers, they often have a wide knowledge of things; they are people who care. And there is a reason for that, because to create symbolic figures and to bring about interruptions of the norm—which is another thing that art does—you need philosophical ideas, and in some cases scientific ideas as well. You might do it spontaneously at first, but then you start to reflect on what you are doing, and you need to draw on philosophy, science, and other disciplines, psychology, geography, economics, etc. I think cultural practice involves all these things. After you engage with social movements and go through a period of activism, it is quite important to evaluate. “We had ideas, we wanted to achieve something, we had utopias, but what did we really achieve? What did it amount to among those who support us, and among those who don’t really support us, who are against us?” It’s important to evaluate the kinds of reactions you produce, otherwise you just go on contributing to things unconsciously. And there is a lot of unconsciousness in society already, which can obviously produce very bad results.

TMV: Is the Occupy movement one example of how you can make this change happen or was it a failure?

BH: I don’t think Occupy was a failure. There have been very good results, and interestingly, the results were attained by realizing that there was a limit to the first attempts. The defeat is clear: the police and the media forced the movement down, that happened to Occupy Wall Street and to and all the movements that derived from the Egyptian uprising. But the only real failure is the failure to articulate the limits of the movement in both discourse and in practice, and to point beyond those limits.

The Occupy movement in Spain is particularly interesting: The Spanish version of Occupy, the 15M or 15th of May movement, did not just produce a new political party. After it ended, it was replaced by more middle- and long-term movements, which are often known as municipalism. In particularly, in Barcelona, it was around the housing issue that generated an extraordinary form of activism. Protest is great to figure out what’s wrong and what to do, but then you have to do it in a durable way, with lasting effects. They were actually able to get housing back for large numbers of people, through direct action followed by negotiation with the banks. This is the most advanced form of practice. In Spain that kind of movement became highly articulated as an alternative position in society, and it extended through the cultural sphere to the sphere of political activism, to universities, and a broad spectrum of alliances in Spanish society. Ada Colau, who was the public face of the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages (PAH, Plataforma de Afectados por Hipotecas), achieved the transition from being a counter-globalization activist to becoming a municipal politician and the elected mayor of Barcelona, and their whole administration is a broadly collective activist thing. After the May 15th movement (2011), members of the PAH got elected to the Spanish parliament in 2014, so you have a real political force whose base is in community activism, not just anarchist protest, nor just a new, top-down, televisual party like Podemos. This is because the Spanish actually spent a long time with thinking about this issue of the commons, of the common good, what the nature of social cooperation is, how it produces benefits for the people, how it furthers the goal of equality in society. All these questions have been talked over very extensively, both theoretically and practically, and so we can learn a lot from the Spanish.

TMV: You mentioned that the Anthropocene public space, whose territory is the metropolis, is not a single place but a “condition of relational awareness”3 that requires broad participation. Would the Spanish PAH be an example that you also want to achieve in terms of the Anthropocene public space?

BH: Yes, because beyond the most immediate problems, like losing one’s house or job, there are larger and larger problems, and ultimately the problem of climate change. At that level, it’s not that one doesn’t have a house, but instead, the devastating feeling that one’s children don’t have a future. It starts to weigh on people with a similar sense of immediacy, it becomes a burning issue. Then you have to think, what can I do now to help the next generations to have a viable future? You can see what will be done under the neoliberal mentality: the richest people will create gated communities, they will build strong buildings against the wind, the sun, and the storms, they will fund private police to protect them from poor people, from refuges, and basically from conditions of civil war. Anyone who wants their children to grow up in a different society has to think how we can reorganize now, to provide different conditions in the future. It means asking yourself some questions: “What do I produce, what is my labor going towards, what result does it have in the world?” These are real political questions. They are not questions about interrupting a séance in parliament or pointing out one corrupt business deal between elites; they are broader questions. Conditions will change and the way we adapt to those changes is important. People who grasp this importance can work on much better futures. If we go blindly into the future, we will get what’s already coming to us, that’s very predictable.

TMV: But that is a possibility too.

BH: Of course that is a possibility too.

VTM: In the case of the map, it is easy to see how the poisonous petcoke affects people’s life in the area, but on the global scale, the labor on which the elite’s and the managerial classes’ wealth depends comes from other parts of the world, so we don’t really face those problems. I find it difficult to see how change can be effected in global terms, if the first step or protest comes from the people who suffer, and then change can be effected by the intellectuals who help, but they do not see or meet directly those parts of the world where people really suffer from global exploitation.

BH: That’s not really true. You are describing the global balance of power that has led to the growth of the current professional-managerial class, by which I mean the so-called middle class that serves the elites. But that is only about 20% of most societies. Basically, in all the big cities around the world, you have a core area that is wealthy and protected, but simply by walking, you can leave that core area and see how the other social classes live.

TMV: You mean change will start from the neighborhood and that will spread?

BH: I mean that one thing that artists and intellectuals can do is to actively enlarge the scope of social perception, and in that way, reveal why changes are necessary. For instance, if you get into a car, you can go see where they are planning to build the big nuclear power plant here, in Hungary, in the upcoming years. In the US, since the invention of “fracking,” we are subject to extractivism almost everywhere in the country. Anywhere you go, you can see what neo-colonialism looks like in your own country. In Chicago, anybody who cares can see the effects of extractivism in their own life, you can see the brutality of the social relations, you can feel it, you can be affected by it. In the city of Chicago, it just depends which direction you walk, you can see the powerful financial center, but you can also see industrial devastation, extreme poverty, violence, drug addiction, and so on, just by walking in another direction. And I don’t think it is any different in Budapest. The global system increased the size of the bubble in which the professional-managerial classes live, but there is always a world outside, very near. The ultimate question is how to replace neoliberalism. It is not just an accidental discourse of corruption, it is a deep philosophical discourse about what society is. It is not just an inarticulate greed you can dispel or point a finger at, you have to go to convince people that there is a better world.

TMV: You are visiting the Anthropocene Campus at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. They have initiated the Antropocene Project, a trans-disciplinary research to find new ways of educational methods and content to respond to the challenges of this era. Is it why you take your map to Berlin, to spread the idea?

BH: Yes, and mainly to learn from other people. The idea at the Anthropocene Campus in Berlin is that people come from different universities and professional or artistic practices, they all want to help in this vast problem of climate change, and everybody there is hoping to learn something. We have to learn from each other, we have a desperate need to discover the resources that could help us to articulate a better view of the future, and not just a predictable apocalypse.

TMV: So, it is connecting, learning from each other, and triggering change.

BH: Yes, if we’re lucky!

About the author

Tünde Mariann Varga is an Associate Professor at the Department of Art Theory and Curatorial Studies, The Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Budapest. Previously she was a research fellow at the Department of Comparative Literature, ELTE, Budapest. Tünde Mariann Varga holds MAs in English and Aesthetics from ELTE, and a PhD in Comparative Literature from ELTE. Her field of interest includes visual culture, art theory, contemporary art, contemporary documentary, curatorial and museum studies. She teaches art theory for students of art.

Notes

- Will Steffen, Paul J. Crutzen, and John R. McNeill. “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?” Ambio 36/8 (2007). http://www.efn.uncor.edu/departamentos/divbioeco/otras/ecolcom/compendio/steffen_07.pdf ↩

- Brian Holmes. Escape the Overcode: Activist Art in Control Society. Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, Zagreb: WHW, 2009. https://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/01/19/book-materials/; Brian Holmes. Profanity and the Financial Markets. A User’s Guide to Closing the Casino. 100 Notes, 100 Thoughts: documenta Series 064, Kassel: documenta and Museum Fridericianum Veranstaltungs-GmbH, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012. ↩

- Brian Holmes. “Driving the Golden Spike: The Aesthetics of Anthropocene Public Space” (unpublished manuscript). ↩