According to Mexico’s Ministry of Public Safety and Civil Protection, on average more than 10 women were killed every day in the first half of 2021.[1] Out of the 1,899 crimes, only 508 were considered a feminicide and yet,[2] the rate went up compared to the same period in 2020–a year that, exacerbated by the pandemic, had already seen a rise in domestic violence, that mostly affects girls and women.[3] In Mexico, around 90% of all crimes are not reported, thus these figures are likely underrepresenting the extent of the violence against women. Furthermore, gender equality advocates and women’s rights organizations have shown that the crime of feminicide is further erased as judiciary agencies may or may not classify the event as such during the different phases of the investigation process. Miscategorization, manipulation, and obfuscation of state and federal statistics not only generate misinformation but can also, in turn, lead to the defunding of existing programs and services that work with the victims, and prevent the creation of new ones. As a result, there is a larger lag to address the gender violence crisis.

In the early 1990s, feminicide was perceived as an issue specific to Ciudad Juárez (in the state of Chihuahua that borders with the US). Initial reactions to the atrocious killings of women associated them with organized crime but, as the National Citizen’s Observatory for Feminicide notes, across Mexico, these murders result from historic inequality and violence that translate to unequal power relations and misogyny. In 2009, following recommendations from the Inter-American Court for Human Rights, gender equality advocates and women’s rights organizations pushed for the inclusion of the definition of feminicide in the criminal code, which progressively took place, covering all jurisdictions by 2017. Feminicides are defined as “homicides motivated by gender-based reasons,” where “gender-based reasons” refer to the structural subordination of women. Gender-based violence includes a wide range of crimes, like woman trafficking and rape among others, which too have increased in Mexico in the past few years. More subtle forms of violence and inequity also abound in Mexico and remain outside the legal scope, such as the case of 8,000 pregnant girls under the age of 15. Or the fact that out of the indigenous population that graduates from middle school, only 25% are women. Mexico is among the countries that have the lowest number of women in the workforce even though the number of women attending and graduating from college has grown considerably.[4]

In spite of growing research and official reports that show the severity and pervasiveness of gender-based violence, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador continuously diminishes, disregards, and criminalizes the feminist movement as one coopted by his opponents. On March 7th, 2022, on the eve of International Women’s Day, he declared that the women’s protest the next day was intended to destabilize his government, he accused participants of wanting to portray Mexico as a “country on fire” to the world, and he invited women protesters to act peacefully, as if they weren’t already in a fiery situation.

It is in this context that women’s protests have continued to gain traction and attention with a considerable increase in participation in 2019, when the dire situation saw a plethora of feminist and women’s collectives arise from different socio-economic and cultural contexts, as well as from various disciplinary fields, including the art world. This is the context the collective Restauradoras con Glitter [Restorers With Glitter] also emerged from.

This interview was recorded in writing and via Zoom in December 2021, in conversation with Sofía Riojas Paz.

Valentina Sarmiento Cruz: In the second half of 2019, almost immediately after publishing a statement on social media, you gained an impressive amount of attention on social media and in news outlets in Mexico City. Soon after, coverage expanded throughout the country and the continent. Now, over two years later and for this primarily European readership, can you tell me who signed that initial statement and why?

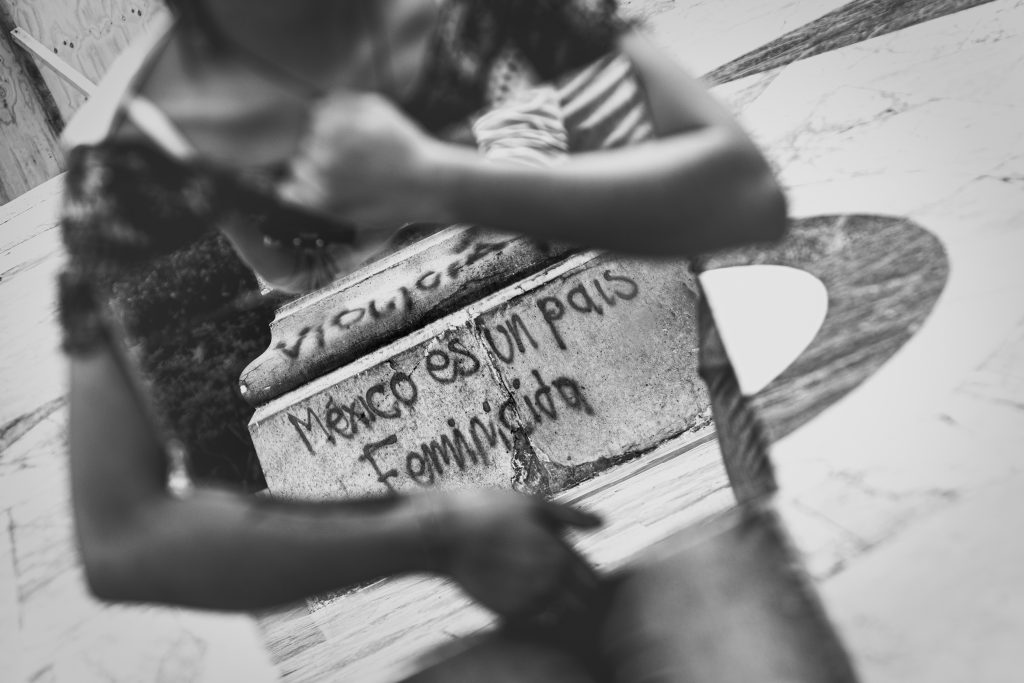

Restauradoras con Glitter: The collective Restauradoras con Glitter was born in Mexico City in response to the numerous smear tactics used by the media and by certain political actors against the protest organized by women’s groups and feminist collectives on August 16th, 2019 – labeled in social media with the hashtags: #Me Cuidan Me Violan #NoMecuidaLaPolicía #MeCuidanMisAmigas[5]–, denouncing numerous cases of sexual and gender violence by the police nationally and in metropolitan Mexico City. More specifically, the smear tactics targeted the protesters because of the messages some of them inscribed on the surface of the plinth to the Ángel de la Independencia [a revered celebration of Mexican Independence].

The accusations leveled at the demonstrators that accused them of “destruction” and damage to the national cultural heritage caught the attention of colleagues professionally dedicated to its study. Given the viralization of the narrative by the media, the spread of exaggerated, insufficient and inappropriate information, and the failure to identify the main cause of the demonstration – namely, alarming gender violence – a call was made within our field of cultural heritage restorers to consult with and put together a statement. This first moment gave the collective the first word in its name. Although the call was immediately extended to other professions working for the preservation of the country’s cultural heritages, we decided to only keep “Restauradoras” [in the feminine form of the word] due to the major presence of women restorers in the collective and because it is a predominantly female profession.

We then added the word “glitter” to align the group’s identity with the demands and positions that called for the demonstration on August 16th. That day, demonstrators reclaimed glitter as a representative element of the protest because on August 12th, in Mexico City, a protester threw a fist-full of fuchsia glitter on the head of Jesús Orta, then Secretary of Public Security. Restauradoras con Glitter decided to appropriate this symbol of feminist protest and use it as an emblem of deconstruction of hegemonic structures and as a celebration of the richness and variety of the female experience. Those of us who decided to join the collective subscribe to the struggle because we have lived through and experienced gender violence in our lives and daily activities. We know that the protest points to an old, deep, complex, and aggravated problem that continues to claim the lives of women every day.

Faced with this landscape and newly formed, the collective wanted to present the authorities and civil society with a series of reflections regarding the interventions made on the plinth to the Ángel de la Independencia. We addressed the president of the republic, Mexico City’s mayor, feminist groups, and organized civil society with this text, from which the five main takeaways follow:

- The means of expression of the protest are legitimate and should be taken as a guideline to generate reflection in society, coordinated between the civil society and the authorities.

- The annulment of a part of society through gender violence is a notable detriment to the social fabric. Cultural heritages are disconnected from the social fabric if the latter deteriorates.

- The complaints inscribed onto the monument do not present a risk to its integrity. Therefore, the inscriptions do not hinder the monuments’ conservation and should not be exploited to criminalize the protest or minimize its main cause.

- The complaints are a form of expression and denunciation by a social group that we must integrate to the social, cultural, and political mechanisms of the present. For this reason, these complaints must be considered as part of the historicity of the monument and before erasure, they must be thoroughly documented.

- The result of the documentation will allow a path of reflection for society in general, with the aim of generating viable and effective strategies and solutions in the short and medium term that reduce and eventually eliminate gender violence altogether.

With these points as principles, we created Restauradoras con Glitter to support the struggle for women’s human rights and to call out the lack of attention to the urgent cause: gender violence. Once the above points had been communicated and received positive reactions from civil society actors and certain governmental bodies, the collective decided to consolidate itself to become part of the Mexican ‘glitter revolution’ in the long term.

VSC: This is an incredibly helpful overview of the context that gave origin to the collective. Can you speak about Restauradoras con Glitter today?

RCG: Sure, we are an independent and nonpartisan Mexican feminist collective, made up of women specialists in various disciplines, actively dedicated to the study and conservation of cultural heritages. As such, we believe that conservation must be based, inexorably, on the well-being of the creators-users of said heritage.

We employ an empathic, plural, and flexible notion of cultural heritages based on the identification, protection, recovery, interpretation, and dissemination of their elements: tangible objects, their creators-users, and, above all, the dynamic relationships that are established between them throughout history and that provide them with meanings that manifest themselves in multiple ways. Therefore, and although we do not encourage the alteration of cultural heritages, we believe that their resignification is an inescapable, healthy process that can lead a society to become aware, and act constructively in the face of its current needs. In the case that we are currently dealing with, this refers to the need of becoming aware of the ongoing gender-violence crisis that women in Mexico are experiencing and suffering from, in order to take actions aimed at its resolution.

In short, based on the aforementioned foundations, the collective is part of the fight to eradicate systematic, normalized, and unpunished gender violence, prioritizing violence against women. This purpose has encouraged the actions of the collective to always be linked with those of other sister collectives and civil society organizations that pursue the same objectives.

VSC: Since the consolidation of the collective, are its members performing art restoration/conservation differently? Have you adopted any actions, changes, modifications, omissions for your work as conservators within the collective?

RCG: The collective has brought us together as professional practitioners and as women, that is, it has posed significant dilemmas in the way in which we conceive of ourselves in both scenarios that is necessarily inclusive and that implies assuming ourselves as active political subjects. Given this activation, we have felt and thought that it is essential to reformulate several of the concepts with which we approach and do work on a daily basis in our fields. In the case of August 16, 2019, the message worth recording, studying, and preserving were the denunciations made on the plinth to the Ángel de la Independencia, which would commonly be treated as “alterations” or “damages.” Instead, we think that these are fundamental traces of women’s history in our country; they are a living sample of a historical moment that must be highlighted; they contain a message that cannot be forgotten. The reclaiming of public space, the transgression of the hegemonic values of the State, and the interpellation of them, evoke a turn that leads us to question what we conserve/restore, for whom, and whose narrative we are perpetuating with our daily work.

So, after August 16th, 2019 and many other events throughout our country, the demonstrations of organized women from civil society (whether they consider themselves feminists or not), offer a counter-discourse to what “patrimony” is. Therefore, our conceptual proposal has focused on the search of other categories that bring us closer to explaining this phenomenon through narratives that deviate from official or traditional forms. The term “cultural heritages” fits this approach which we’ve been working with, because it includes notions raised in the founding documents of conservation-restoration as a discipline, such as those included in the Venice Charter from 1964:

“Imbued with a message from the past, the historic monuments of generations of people remain to the present day as living witnesses of their age-old traditions. People are becoming more and more conscious of the unity of human values and regard ancient monuments as a common heritage. The common responsibility to safeguard them for future generations is recognized. It is our duty to hand them on in the full richness of their authenticity.”[6]

With “cultural heritages,” we then refer to that message from the past that is transmitted to future generations and that doesn’t necessarily fall within the lines dictated by the hegemonic order of the State or of other spheres of power. The term “cultural heritages” allows us to look at other expressions, other forms, and other discourses that, although continuously minimized and/or censored, are necessarily part of who we are as a society, with our disputes, tensions, contradictions, and diversity. The term “cultural heritages” allows us to turn our attention towards those “silences and absences,” it allows us to understand, in the present tense, that the narrative of protest and resistance must be made visible and that it suggests a new approach towards memory and its traces, its stories, and counter stories.

VSC: So we can talk about a “before” and an “after” in the way that you all practice cultural heritages restoration, art history, or any other discipline your professions are based on. This is reminding me of another interview, from late 2019 or early 2020, during which a member of the collective corrected herself after using “patrimony” and switched it for “cultural heritage” to avoid the use of a word with a patriarchal etymology. For me, moments like that, require a special attention to and an acknowledgement of how we can all help build alternative stories (and realities!) to those passed down to us that consider and contain a single perspective, a single history with a capital H. The shift in the terminology you all endorsed was already producing a disciplinary change. Hence the importance of language… it’s fundamental in the creation of a discipline, how it is taught, learnt, practiced.

RCG: Yes, but it’s not language only, it’s how we create and practice the use of a conceptual framework that combines discourse and practice. And it is also complicated because this is our job, so professionally, things are still called the same. Curricula are still called the same, procedures are still called the same, and many things that have to do with the institutional order are still called the same. That is, we can do some engineering and some things are changing, but it has been very slow. We have to be jumping between playing with language like that, and using the same old names because yes, we work in institutional spaces, and then go back and see other ways of doing things and so on. It’s challenging.

VSC: Certainly, and so you use a particular hat here and a different one there because all of your identities are suddenly in tension as well.

RCG: Yes, exactly, and our new approach has changed the way we face many issues in our field. It has especially allowed us to move towards an identification and highlighting of the importance of women’s struggle in Mexico, to direct our gaze towards those gaps in the representation of women in many aspects of public life in our country, and to point out how gender violence prevails and pervades every day in our country. The monuments in the public space and the public space itself have become the scene in which these asymmetries, differences, violence, and injustice have been expressed, and for reasons that we do not find logical, the transgression of inanimate goods (such as monuments and other cultural heritages) causes more scandal and concern than the tragedies that are inscribed onto them. It has been our commitment to point out over and over again that the lives of women are more important than walls; that, unlike the lives of women who are or have been victims of gender violence and feminicide, material goods can be restored.

VSC: Perhaps, as you mentioned in a previous conversation we had, you are professionally art restorers, yet currently also seeking to restore the social fabric… or at least signaling that it urgently needs repairing.

RCG: Right, our vision about the importance of cultural heritages has not changed: we believe that they are fundamental witnesses of history, but the focus on women’s struggle in Mexico is life itself–life that is at risk for all women at any time and at any place. As stated in the Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the cultural rights of women (A/67/287, 2012):

“Active engagement in the cultural sphere, in particular, the “liberty to contest hegemonic discourses” and “given” cultural norms offer women, as well as other marginalized groups and individuals, crucial possibilities to (re)shape meanings. It also helps to build central traits of democratic citizenship, such as critical thinking, creativity, sharing and sociability.”[7]

We agree that the reclaiming of “patrimonial” public spaces is a way to promote these democratic changes for the sake of a more just, more equitable society, in which we feel represented. We deeply believe that institutions, the media, and society in general, must fundamentally reformulate the way in which they conceive of the problem of gender violence and the role they play in perpetuating narratives of stigmatization, criminalization, and hatred towards women. In this sense, our relationship with the institutions of the State has changed in that we actively advocate for the reformulation of concepts and of procedures. We believe that women’s voices must be heard at all levels.

One of the strongest points that I think allows us to share our reflections in so many places is that we are thinking about our own work: we do not intend to indoctrinate anyone, rather it has been a process about questioning what we ourselves have been thinking and doing since that event in mid-August. Back then, a lot of people were saying “poor, suffering stones,” while we were wondering why the drama focused on the material when clearly the issue is that atrocious crimes are committed against more than half of the population. We are talking about impunity. We knew we had to focus our and everyone’s attention on what is important: the denunciation, the demand for a life free of violence. Yet, it seems that by highlighting the message of the protesters inscribed over the monuments, and that by advocating that such alterations should not be removed until they were addressed, we were betraying the disciplinary principle; as if we had taken an institutional vow to protect heritage above all things. It also seems that it is a betrayal not only to the discipline, but to the nationalist discourse as well – a nationalist discourse that built its meanings, identity, and cultural identities throughout the 20th century. This is important to point out because questions around official discourses are also very relevant to our times, as are the disciplinary ones, in this case, of a discipline that was founded in the post-war era – a period very much of the 20th century. Hence, questioning a singular understanding, a singular way of living, and a singular way of representing it is very much from this time, our time. We are witnessing the collapse of hegemonic State narratives, of the State itself at various levels. We are even witnessing the collapse of the capitalist system, and then we reach this point where we have to question the discourses that sustain it all because everything is discourse. The “patrimonial,” in reality, is all discourse, it does not exist and it’s at this point when we have to question the discipline, the institution, the official narrative. This is what is interesting on many levels for us. Why? Well, because we are our own subjects of study.

VSC: You see this as a moment in history where there is an opportunity to ask yourselves whether some of the symbols that have been used in different discourses or narratives are relevant in the same way as when they were conceived. And an opportunity to avoid an automatic perpetuation of the taught discourse and practice, to help inform different and new narratives.

RCG: Exactly. A colleague recently told us that in a feminist world we wouldn’t need monuments and, as restorers, we would have to do something else. And it’s true! We find it very important that these kinds of questions challenge us in that way, in a deep way.

VSC: In an existential way.

RCG: And we’ve seen these processes in other disciplines: anthropology has been going through 40 years of self-reflection and self-critique, geography as well, but also physics. That is, all these disciplines were born and developed by being useful to somebody. Plus, it is a process that would be very difficult to do individually. It has to be done collectively because there is a lot of resistance, even within ourselves. Sometimes I don’t even want to think about it, I just want to keep thinking about rocks and stones because, otherwise, it is all very challenging, very disturbing. But we do it, right? Over and over again. And I feel that we have never had the opportunity to pause because it is something that people have asked from us in different spheres. There is a sort of thirst for talking about these issues. So, this work has become a life project.

VSC: Indeed, it’s also thought-provoking and telling to see where the interest is coming from and how some organizations, institutions, and individuals are offering platforms for discussions with collectives and people with similar goals as yours. Following the disciplinary analysis you were just doing, I think it’s worth considering the very name of the discipline of “conservation” or “restoration.” It entails a notion of originality and purity, and the objective of eluding the passage of time on the objects, doesn’t it? Therefore, there is a rejection of the possibility of any external social forces that could “damage” or just change the initial meaning and materiality of the monument or art work.

RCG: Terms like “purity” or “authenticity” are very controversial. In fact, many international documents speak about just this subject. Regarding authenticity, the Nara Document on Authenticity from 1994 is one of the most important ones. One of the points raised since the 1930s in this debate is that we must ask what authenticity means and who authenticity is for. My favorite example is the Pantheon in Rome: it’s thousands of years old and it has been everything, that is, everything. And at some point, certain decisions were made to remove various elements that were already hundreds of years old. Someone had already claimed that only the very original or initial pieces were “authentic.” In this sense, they rejected the idea that the elements that were removed were significant parts of this place’s “life story.” Something that I know was discussed a lot during the 20th century, and still is to this day, is that there is no one authenticity, but rather there are several moments in the history of these objects that tell us about the different aspects of the cultures that produced them. So, we have looked at many of these debates and documents as guiding principles of our discipline and, at no point do they say that sites of heritage or art objects must be “clean” or “perfect.” Instead they suggest to look at the different moments that “x” society has had at those sites and, in turn, how those spaces have been transformed by society.

In our initial letter from 2019, we claimed this as a basic principle to our understanding of the events: monuments, and cultural heritage in general, are useless if civil society does not signify, re-signify, despise, or interact with them. That is, if there is no dynamism they are nothing, they do not have a value per se. So that is one of the things that we have been very emphatic to say, to discourage the obsession over materiality, to re-focus on what is happening as context and hope to encourage and help create change in the narrative. And what I can tell you from these past two and a half years is that we have seen that change in the narrative a lot – that is in the spaces where we’ve been invited to share our work, especially in universities. It’s impressive to see a change there. We have also seen it because we have collaborated very closely with the organized women and students who have taken over and shut down the different schools recently [to demand different basic conditions, accountabilities, and actions from the institutions]. And then, on the other hand, we have media interviews and it is as if nothing has happened. Time stopped. It is the same criminalizing discourse against women.

VSC: Well, the way you were describing this dynamic relationship with monuments and cultural heritages, sounds a bit like the same tool the collective is using for the discipline: you took an excerpt from the Venice Charter and said “why don’t we reinterpret this ‘established,’ maybe even prestigious, text to our advantage?” In other words, and I’m thinking about the coming together of your activist identity and your restorer identity, even if the collective hasn’t developed an explicit petitions list on what to change in and about the field, you are modifying it anyways. The changes are happening as a consequence of you all as practitioners re-signifying the discipline in your doing. And your practice goes beyond your work as restorers. Some of you are docents as well, and so the changes that you’ve seen in students from universities are also welcomed by people like you.

RCG: It’s a bit like trying to experiment with our own life. As for internal organizations, some of the places where we work, much progress has been made in consolidating spaces by and for women. Many fundamental things must be changed, reformulated from necessarily feminist lenses, from different feminisms. Not feminism as dogma, but as a strategy that allows us to question what we have replicated, why we do what we do, and the ways in which we do it. We must see that the silences are political, that omissions are political, and question all these official discourses, museum discourses, discourses of interventions in public spaces—who is being talked about, who is not being talked about, who is represented and who is not, what spaces are open, what spaces are closed. That is something we have seen change, and not only in the classroom.

We have witnessed how these new discourses and ways of making are beginning to permeate different spaces and that has also been very impressive because, when we first came together as a collective, nobody or almost none of us saw themselves as feminist. And, again, it’s not that we now see ourselves as feminists in a dogmatic way, but based on our different readings, shared self-reflections and self-questioning, and after learning a lot from other colleagues, collectives, and organizations, we don’t see many alternatives: seeing things without this feminist lens is now impossible! Hence, we’re constantly extremely uncomfortable and pissed off in our work spaces, in our interpersonal relationships, in our going about in the world, but we also have this very enjoyable thing of knowing that we are in it together.

VSC: Can you speak more to that, “being in it together”? How do you work together or carry out internal processes?

RCG: We work together in many different ways; exchange is always present. However, the invitations to reflect in other spaces with colleagues from all fields, both academically and on the streets, keep us actively learning and questioning everything. The truth is that we have learned most of the things about feminisms as we go along. We did not all have a theoretical basis, nor did we have activist experience, so it has been a process of building along the way both individually and collectively within Restauradoras con Glitter, and also with other groups and colleagues with whom we have had the enormous fortune to coincide. So, in sharing spaces for dialogue and mobilization, we have met other women who, individually or collectively, promote actions to make visible the ravages of patriarchal violence and propose ways to build scenarios of peace. We mutually support and invite each other to collaborate. We believe in that form of partnership, learning, and support. Far from rejecting leaders, we believe that the cause and struggle are collective.

Something that is very important as well, that I very briefly touched upon earlier, is that we are a professional field of around 80% women. Therefore, our workspaces have now become our spaces of… perhaps not activism, but of resistance, or of activation, or of solidarity—spaces where these features were not totally nonexistent before, but were perhaps a little diffused. Now, something that we really like to do is to think about how we can use or apply these ways of organizing and the alternative structures we are learning about “outside” in these workplaces because we are also super OCD, very systematic.

VSC: Well, I personally think that can be a great quality and even a “must” in the work you are doing. To begin to close, as a collective, what have you come to see as your greatest strength? And what is your greatest fear?

RCG: Our most effective tool is that we like to talk a lot. Actually, yes, we have found very good spaces for exchange by having the desire to share what we think and open a dialogue about what occupies our minds and trigger self-questioning. Beyond seeking to indoctrinate, we have found it important to share our reflections and concerns. And our biggest fear is that they continue to kill eleven women a day and nobody does anything.

VSC: Right. The year you founded the collective, an average of ten women were killed on a daily basis. The average increased to eleven per day in 2020 and decreased back to ten during 2021. What is the future of glitter restorers? Any short-, medium-, and long-term objectives? Or post-pandemic/lockdown goals?

RCG: We are working on many things for this new year. Our main idea is to continue working and work even harder and in a more structured manner. We have many collaborations in sight, and we believe that we must do everything collectively anyways. We are in a moment of change, of fundamental change in terms of our structure because we need it and because we also wish to do many other things. We get invited a lot to talk and share in different spaces but we wish to generate those spaces ourselves, too. We wish to bring certain topics to the table, we wish to seek creative ways of thinking about other worlds. So, I think we are at a point of maturing certain projects and… I’ll just say it like that also so I don’t jinx it! But I promise, we’re working very hard!

This interview was recorded in Spanish and was translated by Valentina Sarmiento Cruz.

[1] Secretaría de Seguridad y Protección Ciudadana [Ministry of Public Safety and Civil Protection], Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública [Executive Ministry of the National System of Public Safety], “Información sobre violencia contra las mujeres. Incidencia delictiva y llamadas de emergencia 9-1-1. Información con corte al 30 de junio de 2021. [Information on Violence Against Women. Criminal Incidents and 9-1-1 Emergency Calls. Information as of June 30, 2021]” 14, 26. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1VRwhF9yFw3RjQc_FYpluRrLcraUXIFEs/view.

[2] Ibid.

[3] According to UN Women in Mexico, domestic violence against women increased by 60%, as recorded by their hotline. Source: Margarita Alcántara, “Violencia doméstica contra la mujer aumenta 60% en México durante la pandemia [Domestic Violence Against Women Increases 60% in Mexico During the Pandemic],” Forbes Mexico, July 17, 2020, https://www.forbes.com.mx/women-violencia-mujer-hogar-aumenta-60-pandemia/.

[4] Information from the report “Danzar en las brumas [Dance in the Mist]”, referenced in Beatriz Guillén, “Joven, mujer y latina: los datos sobre desigualdad que revelan por qué siguen las protestas del 8-M [Young, Woman and Latina: Data on Inequality That Reveals Why the 8-M Protests Continue],” El País, March 8, 2022, https://elpais.com/mexico/2022-03-08/joven-mujer-y-latina-los-datos-sobre-desigualdad-que-revelan-por-que-siguen-las-protestas-del-8-m.html.

[5] The hastags can be translated as follows: #TheyLookAfterMeTheyRapeMe; #ThePoliceDoesn’tLookAfterMe; and #MyFriendsLookAfterMe.

[6] International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter- 1964), (Venice: ICOMOS – International Council on Monuments and sites, 1964), https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf.

[7] United Nations (General Assembly), “Cultural rights of women – Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights,” Sixty-seventh session Item 70 (b) of the provisional agenda, “Promotion of human rights: human rights questions, including alternative approaches for improving the effective enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms”, 2012, p.10, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N12/459/30/PDF/N1245930.pdf.

Valentina Sarmiento Cruz is an independent writer and researcher ––she earns a living by doing simultaneous interpretation and translation. Her projects and collaborations have been published widely, including in the U.S., Slovenia, and the Netherlands. Currently, she is co-editing a book for Concordia University Press on designer Clara Porset’s writing. Previously, she worked at the Art Institute of Chicago, the University of Chicago, the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, Artforum, and Creative Time. She holds an M.A. in Liberal Studies from The New School for Social Research and a B.A. in Sociology from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.