Nataša Ilić and Sabina Sabolović, two members of the Croatian curatorial group WHW (What, How, and for Whom), and Nikola Vukobratović, the representative of Alerta, Centre for Monitoring of Right-Wing Extremism and Anti-Democratic Tendencies, Zagreb, held a seminar entitled How Much Fascism? in May 2014 in the framework of tranzit.hu’s Free School of Art Theory and Practice. The seminar and the three-part exhibition and event series Art Under a Dangerous Star were part of the international collaboration Beginning As Well As We Can (How Do We Talk About Fascism?), initiated by WHW. The project explores the Europe-wide spread of the extreme right, contemporary forms of fascism, and the possible ways of resistance and intervention. During the seminar G. M. Tamás, András Rényi, Szabolcs KissPál (Free Artists), Ádám Schönberger (Marom), and Márton Szarvas (Helyzet Group and Gólya) held presentations.

Zsuzsa László: Why did you pick fascism as the keyword fort he project? What is the current relevance of the Slovene sociologist, Rastko Močnik’s 1995 book Extravaganzia II: How Much Fascism? from which you borrowed the title for the exhibition that was first realized at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht and Extra City Kunsthal, Antwerp (both in 2012), as well as for the 2014 seminar in Budapest?

Nataša Ilić: The title of the whole project, Beginning As Well As We Can (How Do We Talk About Fascism?), expresses our questions and doubts. We knew that it is possible that we trivialize the term fascism, but we think that it’s better to react and propose it, and form a space where it can be discussed, than to be super-cautious and avoid the issue.

Nikola Vukobratović: There are other terms that are now maybe more current like “rightwing extremism” or “populism.” We still find it legitimate to use this term if we clearly differentiate it from historical fascism. The connection between its contemporary manifestations and the historical sense is the function, which—in the times of crisis—is to provide discipline and stability for a system in an authoritarian way. It is also important to note that fascism is not necessarily a completely closed, anti-democratic system in the way that historical fascisms were, but it is a mechanism that can be present in different degrees, as Močnik pointed out.

NI: In this sense, we use the term soft fascism to describe the tendencies in contemporary nation- states that have to do with governing and the administration of life, which are clearly different from those of historical fascism, but they have certain continuity with it.

Sabina Sabolović: It was crucial for us to pose the question to what degree these mechanisms are incorporated in today’s social and political systems. This is why we started the project with an exhibition entitled Details at the Bergen Kunsthall, to show that these anomalies are increasingly integrated into something that we are totally accepting as normal. Fascism is a loud word that helps us to put these phenomena in such a perspective where we cannot accept them as normal anymore.

ZsL: You mean that the project proposes a critical approach, even towards leftist intellectuals who might consider some of these authoritarian means natural or inevitable? Or at least are failing to protest against them? So, is the project encouraging a critical self-investigation? Could you mention such examples among the artworks exhibited?

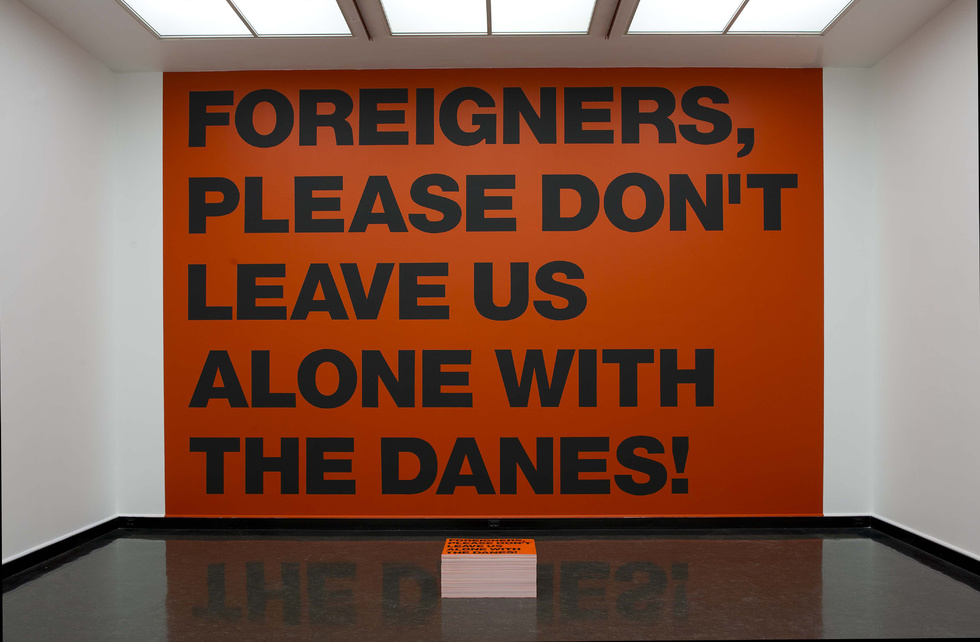

SS: We only hoped to trigger debates and not so much to directly change attitudes. I think the demand to react to daily social and political urgencies is a big burden on artists, as it usually takes time for these topics to get into art production. Most of the works rather presented long-term research on immigration, self-historicization, biopolitics, violence integrated into the social system, the relation of communism and fascism, and they did not represent very specific local situations. Several works from the early 2000s not only had become prophetic and gained new relevance, but they also explored long-term processes. Milica Tomić’s 2009 work is an action during which she was walking on the streets of Belgrade, revisiting the sites of anti-fascist resistance during WWII. The video documenting the action shows a tall, blond woman walking with a machine gun in her hand totally unnoticed; nobody reacts. In the background we hear interviews conducted by Tomić with people who took part in the historical anti-fascist actions that happened on the same streets. The apathy of the passers by is juxtaposed with passionate recollection of the anti-fascist partisans. The artist originally dedicated this action to the young members of the Belgrade Anarcho-Syndicalist Initiative who were accused of terrorism in 2009 for protesting in solidarity with demonstrators in Greece. When we showed this work in Bergen a few months after the Norway terror attacks, it gained a new, intensified local relevance.

NV: In fact it is not simply new fascism in itself that is important to indicate but the impotency of existing forms of resistance. In this sense, with this project, we wanted to explore the class difference in this question: why anti-fascism is of the middle-class, and why lower classes get more and more interested in fascism. We found that this is one of the most important reasons why we are so weak in countering fascist tendencies. As Sabina said, fascism is really a scandalous word, but we need to use it as these contemporary anti-democratic tendencies typically hide their character. For instance, we can have kinds of concentration camps for illegal migrants or for political prisoners, or common sense racism and homophobia, but nobody sees them as revivals of fascist policies or similar to the mainstream anti-Semitism of the ‘30s, because they are applied in a different framework.

ZsL: The Budapest exhibition of the project evoked with its title art historian Ernst Kállai’s 1942 article “Art under a Dangerous Star”. Art historian Éva Forgács, writing about Kállai’s historical text, traced back—relying on Clement Greenberg and Walter Benjamin—the spread of fascism in culture to the joint interest of the political elite and the masses for the preference of kitsch, art that does not need intellectual effort. However, comments on Éva Forgács’s article, as well as the right-wing press, interpret this account as leftist arrogance and as a trigger to accuse leftist intelligentsia with irresponsibility and inconsequence hiding under its cultural supremacy. How can a curator or an artist deal with this class conflict that Nikola also described? What can be done against the growing suspicion and antipathy towards the classical anti-fascist intellectual position and the hostile polarization of European societies?

NI: I think that art alone cannot resolve this problem, as according to the Western art historical tradition, art is an autonomous field and, as such, is devoid of politics. What we can do is to push the boundaries of this understanding of culture and fight for an engaged concept of art that is not based on this autonomy. Culture that take sides, that has ideological clarity. What is important for us, as cultural workers, is not to take an external position, not to act as if all these developments happened independently from us and from our practice, as if we can shout the truth from outside.

NV: The question of whom we can address is a broader issue. There’s a lot of skepticism towards human rights activists and NGOs too. It’s also a challenge for us how to make socially-engaged activism more popular than anti-democratic movements. Based on our experience, it is not enough to organize workshops with similar activist organizations in order to formulate more coherent strategies. We also address young people with propaganda booklets that are to enable them to avoid the traps of right-wing demagogy.

ZsL: At the Budapest exhibition we see works that are based on the gesture and the problematics of addressing (Lilla Khoór – Will Potter: Singular Hungary, 2006; Avi Mograbi: Details, Oleksiy Radynski). They expose very heterogeneous views, and take stands by the juxtaposition of conflicting voices (e.g., the opening performance by Anca Benera and Arnold Estefán). Can you cite examples for such artistic strategies that aim to eliminate the isolated position of art that can address audiences outside the exhibition space?

SS: I don’t think that any of the presented works could propose such a model or strategy that can be exemplified or replicated. The context of the exhibition is very important: it presents the works from a specific perspective. A good example for the earlier mentioned long-term artistic research tackling the process of normalization is the project presented at Extra City Kunsthal, Antwerp by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, an artist based in London and Beirut. He examines the practice of several Western European countries subjecting refugees to voice forensics to identify their origin, decide on their status, and where to return them. The sound installations by Abu Hamdan face us with the harsh absurdity and terror of these examinations, whereas these procedures are part of what is considered a completely official state policy.

ZsL: You mentioned the issue of solidarity in connection with the international collaborations examining fascism as not a very ambitious but still an empowering gesture. The other important message for me was that it really depends on us too, cultural workers, we cannot regard ourselves outsiders, we should not isolate ourselves, and release the field of art from taking responsibility, even if it only means opening up spaces for intelligent dialogue or resistance when there are no other spaces for it.

NI: When talking about solidarity, we have to refer to what G. M. Tamás was insisting on in his presentation: radical equality proposed by communism, in terms of class, race, and gender. Solidarity without radical equality falls immediately in the trap of complacency or moralism.

The interview was conducted and first published on tranzitblog.hu in Hungarian in May 2014

About the author

Zsuzsa László is researcher and curator at tranzit.hu since 2009. She is completing a PhD in Art Theory at the Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. In her research and curatorial activities she explores the interconnections of contemporary and Neo-avant-garde art, exhibition theory and history, institutional critique, and cultural and social history.