OFF-Biennale Budapest is a grassroots, civil initiative, the largest contemporary art project of the art scene in Hungary in the last few years which is realized without applying for funding to the Hungarian state and without using state-run art institutions. After its first edition in 2015, the second OFF-Biennale Budapest is currently taking place, from September 29 to November 5, 2017, in various venues across the city.

tranzit.hu contributes with a program to OFF-Biennale this year too and its online magazine platforms tranzitblog.hu (in Hungarian) and mezosfera.org serve as media partners of OFF-Biennale.

mezosfera.org dedicates its series of articles “Artwork in Focus” to works and projects presented at OFF-Biennale. The series looks at one artwork at a time, and it discusses the topics the particular pieces bring up.

Ágnes Patakfalvi-Czirják, anthropologist, researcher at the HAS Centre for Social Sciences Institute for Minority Studies, discusses the ongoing research project by artist Szabolcs KissPál, which draws parallels between Hungary’s official memory politics since 2010 and fascist-nationalist Horthy-era (1920-1944), pointing to close connections between the “Trianon” trauma after World War I and Hungary’s contribution to the Holocaust.

One of the greatest challenges of the twentieth century was the organization of the masses. There are two basic methods for this: integration and exclusion. Whether it be the development of mass education, the evolution of nation states, the role of popular culture in the manipulation of masses, democratic political participation, or the utopia of organizing communist societies, these methods have precipitated such fundamental changes in the countries and communities they were implemented in, as well as in the fate of the people affected by them, which have left deep and often traumatic marks.

For social sciences nowadays it is evident that memory and memory culture have a substantial role in shaping our conception of the present and that they are fundamental in forming identity. Monopolizing collective memory is a tool used in state and nation building that brings immediate benefit. A number of non-state actors also compete in this (for instance, churches, the organizers and operators of the educational system, the media), as do – with the accumulation of so-called testimonies – common people.[1] The roles of witness, participant, victim, and chronicler continuously change, and become institutionalized even, but they keep reproducing or refreshing the extensive cobweb of exclusion and inclusion.

In Hungary, one of the neuralgic points of the discourse about the past is about the Treaty of Trianon, the peace agreement in 1920, as a result of which Hungary lost more than two-thirds of its territory and more than half of its multi-ethnic population. Another such critical point is the memory of the Holocaust in Hungary.[2] Through the parallel treatment of these two discourses, that have defined the development of the Hungarian society, the exhibition highlights their correlations. Until the regime change, these issues had often been treated as taboo, and only in the final period of the socialist regime and then following the democratic transformation did they resurface publicly. The trauma had not recrudesced until radical right-wing actors began to appropriate the narrative of this sensitive period of the past,[3] revealing its socio-cultural embeddedness. This appropriation took place on several fronts: firstly, the irredentist (aiming to reclaim the territories detached in 1920) and Turanian movements were unearthed;[4] secondly, existing communities and organizations based on solidarity and traditionally maintained good relationships with Hungarian communities across the borders were taken over. Lastly, certain civil initiatives were instrumentalized by political groups and “Trianon” was made to a political issue again, proclaiming authentic national solidarity. In addition to the active presence of the discourse in the political field, a cultural market has emerged on these ideological and moral foundations, operating with products, consumption goods, and subcultural materials, initially in subcultural economic networks and gradually dispersing into the mainstream.

It is this overloaded discourse about the past that Szabolcs KissPál enters with his work presented at this year’s OFF Biennale. In fact, he has compiled a complex project[5] that circumnavigates the theme of Trianon[6] and the national myth in exploring the “survival of the past” and the continuity of practices, visual appearances, use of objects and stories from the past. He seeks to reveal what kind of mechanisms and practices have helped the survival of irredentist movements and anti-Semitism in the post-socialist era, what position these have within the concept of a nation that is being articulated (they have become the leitmotif of the Hungarian “nation-religion”), and how they reproduce elements of the propaganda of the interwar period (for instance, its enemy image, the stigmatization, etc.). The artist initiates a dialogue with social sciences (using archives and other research methods of history, cultural- and visual anthropological field work, the curatorial techniques of museology, practices of archaeology), and through his fictional documentaries, also with the audiences outside the academia, with the radical right wing movement, with actors of mainstream memory politics in Hungary, and with the art scene.

Szabolcs KissPál embarks on this dialogue with a strong statement that he consistently carries through: nationalism in Hungary functions as a sort of nation-religion.[7] The set of devices employed by this nation-religion draws on the traditions and practices of Judeo-Christian culture: it recreates the birth of the nation, its evolution and passion (crucifixion), and eventually its resurrection. All of this involves rituals, leaders, faith and a moral framework. The second part of his statement, however, points out that the mission of nationalism is to exclude “undesirable elements” from collective memory. Drawing a parallel between the processes of the ‘30s-‘40s and those of today, the vast corpus of the trilogy sets this statement in stone.

The first part of the trilogy is entitled Amorous Geography.[8] The central motif of this film is a scale model of the artificial rock installed in the Budapest Zoo in 1902, itself modelled on the Piatra Singuratica/Egyeskő in Transylvania. Originally it served to block the view of a nearby water tower from the meticulously designed landscape of the zoo, but later, after the peace treaty of Trianon, it became a symbol of the lost territories, a manifestation of mourning. The film combines scenes from newsreels of the time as well as captions slides known from silent cinema, but also adding a soundtrack of Hungarian irredentist songs and the song version of the two most important Hungarian national poems, used as anthems.

The second part illustrates the history of the Turul bird as a national symbol. The Rise of the Fallen Feather is also a fictional documentary, a round story from the birth of the nation through miserable passion to rebirth. The Turul is one of the central symbols of the Hungarian nation-religion, activating knowledge about the Hungarian nation through various sculptural or graphic representations. However, the Turul can be interpreted not only as the totem animal of the Hungarian nation, but also as a war symbol, the central symbol of the irredentist movement. The second part of the trilogy explores the rituals and performative events during which this symbol is activated, to eventually resurrect the crucified Turul in glory. The feather of the lost bird is recovered during an archaeological excavation.

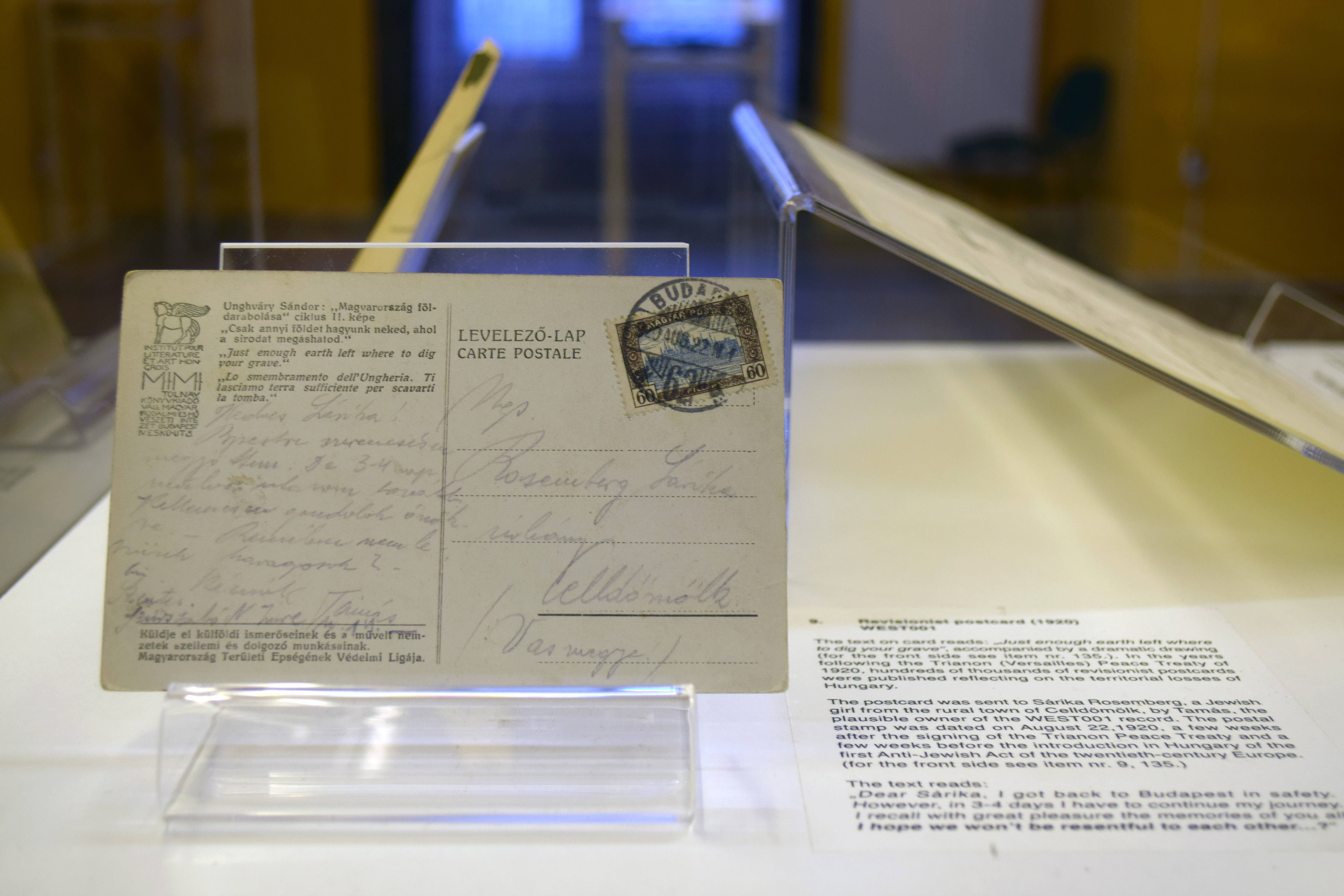

The third part of the exhibition is entitled Chasm Records. With its wealth of objects organized as artefacts in exhibition cases, a complex network of hidden stories and by drawing a parallel between the interwar period and the post-2010 political establishment,[9] this part explains what the artist means when he characterizes Hungarian nationalism as a nation-religion. The majority of the exhibited objects are popular objects of irredentist ideology. The pencil set, the syringe, the brochures, the glass – commodities mass-produced in the interwar period – made it possible to deeply ingrain the ideology and relate it to everyday life. The installation lays out 70 objects, 11 videos defining the context, and 46 printed materials arranged according to different topics (such as “Justice, Religion”, “Memory, Exclusion”, “Rituals/Visions”, “Relics”, “Ideologies”). A single story pops out from the structure of different topics: the correspondence of Sárika and Tamás. Their love affair is the only historical thread in the trilogy in which the characters are able to live a private live, and which inextricably intertwines everything that “Trianon”, Hungarian nationalism and the tragic fate of the Hungarian Jewry stands for.[10]

The relevance of the project lies in its potential to take a firm stand against the exclusory mechanism of nationalist memory politics. Augmenting the imaginary biography of Hungarian nationalism (in terms of landscape and symbolism) and the social life of mass-produced irredentist objects, the subtly revealed moments from the affair between Sárika and Tamás are meant to substitute the vacuum caused by the lack of destinies that have been excluded from collective memory. As Todorov emphasizes in relation to the stake of history and memory politics, the truth of correspondence (the parallel between the interwar and post-2010 period) or the truth of unveiling (the exclusion and anti-Semitic attitudes during the interwar and nowadays ) should be condemned according to political as well as moral criteria.

In KissPál’s work, the judgement is preceded by the intent of comprehension.

[1] To quote Tzvetan Todorov: “To put the past in the service of the present is an act. To judge such an act, we require it to have more than a truth of correspondence (as for historical facts) and a truth of unveiling (as for historical interpretation), for we must evaluate it in terms of good and evil, that is to say, by political and moral criteria.” (Tzvetan Todorov: Hope and Memory: Lessons from the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press, 2003. p. 134).

[2] Between 1941–1945, 56-57% of the Hungarian Jewish population – about 500 thousand people – fell victim to the Holocaust.

[3] The book by Ignác Romsics is an apt summary of the period hallmarked by governor Miklós Horthy (1920–1944).

[4] To understand the history of the Turanian movement at the onset of the 20th century, Balázs Ablonczy’s new book is indispensable.

[5] The third part of the work was commissioned and the complete trilogy first exhibited at the Edith Russ Haus in Oldenburg in 2016.

[6] By today, the notion of Trianon stands not only for the peace treaty signed on 4 June 1920 at the Grand Trianon palace in Versailles, causing the break-up of the historical Hungarian Kingdom, but – in a broader context – it also encompasses its consequences (e.g. the fate of Hungarian minorities who ended up outside Hungary), and its antecedents (e.g. issues of ethnic minorities prior to World War I.)

[7] The notion of “nation-religion” is analysed at length by historian András Gerő in one of his texts. The exhibition’s material has very similar foundations: “It assumes that the nation is a community. It hallows this conceived community and creates the roles and symbols that were characteristic of the original world-wide culture. The nation can have a father, a savior and a Judas. The nation can have a prayer (anthem), it can have an identity according to a combination of circumstances and it can have martyrs, saints, and sites considered sacred. The nation-religion can have all the appurtenances pertaining to the original religion. The most important feature is that one must believe in it. It is this faith that activates it.” (András Gerő: Nationalist Illusionism) The concept of nation-religion was adapted by Elemér Hankiss to Central Europe from the sociological theory of civil religion.

[8] Territoriality is among the most prominent research topics of nationalism studies. Nationalism represents the “one culture one state” principle as the dominant norm, dividing Earth into nation states. To stick with Hungarian examples, the cartographical depictions of the territory of historical Hungary demonstrate the same dominant norm originating in nationalist ideology. By now, this norm not only comprises irredentist ideologies, but also stands for the act of solidarity with Hungarian communities across the frontiers. In addition to all of this, national space in KissPál’s work is also a reference to the close association of blood and motherland.

[9] The venue of the exhibition is exceptional in this respect as well. On the one hand, the Institute of Political History serves the research and preservation of the intellectual heritage of the Hungarian left; on the other hand, its headquarters are right across from the Parliament, in the former building of the Royal High Court. On account of its scathing criticism of the current regime, the exhibition was rejected by the management of a number of other venues.

[10] A moment in the life of the two characters is preserved by an irredentist postcard sent by Tamás – the owner of some of the exhibited objects – to Sára Rosenberg, a Jewish country girl. Two decades later the girl died as a victim of the Holocaust.

Author: Ágnes Patakfalvi-Czirják

Translated by: Dániel Sipos

Photos: Szabolcs KissPál, Krisztina Csányi

Installation views at the Institute of Political History, Budapest