The radical rethinking of the international art exhibition at documenta fifteen was both exciting and provocative. It was bound to—indeed, designed to—create controversy. Ruangrupa’s brilliant strategy mingled the generally separate domains of creation, curation, and reception while firmly centering the Global South as subject of the international exhibition. Judging from the reactions on the ground, which ranged from delight to disgust, it was a rousing success. From the get-go, everyone involved recognized that the historical, post-colonial angles of documenta fifteen had a sharpness that no other international exhibition had managed. Any number of biennials and triennials have played with similar themes, but with none of the verve or challenges one encountered in Kassel in the summer of 2022.

Regrettably, much of this came to be derailed by the rolling series of racism claims. Some of these were warranted (most notably the caricatures of Jews and African-Americans in the panner titled “People’s Justice”), but most claims were simplistic, ahistorical and unfair. As a member of Tokyo Reels, one of the exhibits accused of anti-Semitism, I had a window on the turmoil all this caused within the lumbung of artists. I will write at length about this for a different venue. Today, I want to focus on the two collectives with Japanese connections—Tokyo Reels and Cinema Caravan—as their contrasting positions within documenta hold lessons concerning cultures of willed remembrance and forgetfulness… and their unintended consequences.

Tokyo Reels is a project spearheaded by Brussels-based Subversive Film and led by filmmakers and researchers Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi. It centers on a unique archive of 20 films from the Palestine-Japan solidarity network from the 1960s to 1980s. Yaqubi discovered these prints on a trip to Japan, where he was screening his own work. After the Q&A a scholar of Middle East Studies, Tanami Aoe, introduced herself and invited the Palestinian filmmaker to her parents’ home in the suburbs. There, Yaqubi found a bedroom packed with records from the solidarity networks, including what was left of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s Tokyo office. This included 19 reels of 16mm fictional shorts, experimental films, documentaries, agit-prop, and news reports about various aspects of the Palestinian struggle. To this, a long-time activist added one more documentary to constitute what is now called “Tokyo Reels.”

The Tokyo Reels project explores how these films arrived in Japan, how they were distributed and exhibited, and how they were received. Members of the collective include filmmakers, scholars, and activists from Japan, the US, Europe and Palestine. Like many contributions to documenta fifteen it was a work-in-progress where exhibition was built into the process of creation. Shilleh and Yaqubi moved the prints to Brussels, where they painstakingly made digital scans and complete transcriptions. With the transcriptions, they published a trilingual catalog for each film (they are available on the project’s website). And with the scans, Subversive Film began a process of restoration and reflection. Documenta was part of this ongoing process and featured two centerpieces. The first was a large installation where the films were perpetually screened in whole, in a loop that lasted more than 10 hours. Between each film, Yaqubi and Shilleh quietly comment on what the audience just saw and introduce the next film. Their dialogue is speculative and open by design, putting the thoughtful inquiry of the Tokyo Reels project and its many mysteries on public display. The second major feature of Tokyo Reels’ documenta project was R21 (2022), a montage documentary that draws deeply on the scanned films to contemplate the present-day import of these “subversive films,” their many modes and circulation routes. Tokyo Reels is a complex and stirring archival project driven by contemporary political urgency.

The second project is Cinema Caravan, a Japanese collective based in Zushi that includes artists, musicians, cooks, carpenters and people from all walks of life. Zushi is a small beach community next to the old capital of Kamakura. In addition to running a hostel, coffeeshop, rental workspace and surf shop, Cinema Caravan has hosted a raucous beachside film festival since 2010. Their screen sits right on the beach and is portable, so their activities include portaging it around Japan and the world to stage screenings and parties—thus the “caravan” moniker. Notably, they were one of a couple screening troupes showing films to victims of the triple disaster of 2011 (the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown). The director of Cinema Caravan is photographer Shizuno Rai; for documenta he teamed up with artist Kuribayashi Takashi to create a caravanning installation of light structures made of wood frames and mosquito netting. They moved, unannounced, from site to site during the 100 days of documenta, staging lively, all-night parties with a bar and DJ booth surrounding a mysterious, spaceship-like structure.

Cinema Caravan provided the most spectacular and successful example of nongkron, one of the Global Southern vocabulary terms ruangrupa introduced to destabilize the conventions of the international art exhibit (there is an entire glossary on the website). Nongkron is an Indonesian slang term from Jakarta that loosely translates as “hanging out together.” It involves casual conversation and implies a warm togetherness, as well as the sharing of time, ideas and food. The number of opportunities for nongkron with artists at documenta was astounding; the lumbung press published a poster with a simple list of all the talks, symposia, workshops, screenings, conferences, parties during the 100 days—so many that they had to use microscopic print. Ruangrupa and many lumbung members loved Cinema Caravan for the way they deeply embodied nongkron. The gatherings around their mosquito-net structures were friendly, relaxed, and truly joyous. They were wonderful sites where artists came together with visitors and the people of Kassel.

Cinema Caravan and Tokyo Reels had radically different experiences at documenta. Curiously, Tokyo Reels went largely unobserved while the summer’s accusations of anti-Semitism were hurled this way and that. However, by August, critics pushed it to the foreground and it came under intense scrutiny by the Scientific Advisory Panel construed by documenta’s Shareholders. In early September, the Panel called for the censorship of Tokyo Reels in a preliminary report. Their critique was vague and riddled with inaccuracies. They recommended that the entire installation should be immediately dismantled, just weeks before the end of documenta, which was what the Shareholders and Supervisory Board pushed for behind the scenes—to the righteous resistance of interim director Alexander Farenholtz, ruangrupa, the artistic team, Selection Committee and the lumbung of artists. Needless to say, this was a painfully excruciating experience for Tokyo Reels and all its allies. In stark contrast, Cinema Caravan partied on through the summer. It experienced no political problems because it studiously avoided politics—which, of course, implies a profoundly political stance of its own.

This ambivalence was hiding in plain sight in Cinema Caravan’s installations. The strange, funnel-like centerpiece that people partied around is a 2021 work by Kuribayashi, entitled “Genki-Ro.” One passes a wood-burning stove to enter a tube that wraps around its periphery, leading to a sauna in the center below a tall “smoke stack.” Its conception is odd for a number of reasons. First of all, Japan is a bath culture, so the outdoor sauna feels less natural than faddish and too cool. It feels alien in both shape and conception, especially when compared to Kuribayashi’s more organic works deploying wood, dirt, plants and water. Second, and more importantly, the shape is meant to evoke a specific image: In a virtual afterthought in the catalog’s Cinema Caravan page, the structure is described as “a functioning herbal steam sauna in the shape of the nuclear reactor in Fukushima.”

The title of the piece, Genki-Ro (元気炉), is a play-on-words that goes completely unexplained. It refers to the Japanese term for “nuclear reactor” / “genshiro” (原子炉), substituting the characters ”genshi” / 原子 (“nuclear”) with “genki” / 元気, a common word condensing the meanings for “lively, energetic, spirited, vigorous, healthy, fit, and vital” in two compact characters. Thus, a direct translation of Cinema Caravan’s contribution to documenta would be ”Furnace that Makes You Happy and Energetic.”

I’ll be honest, there was something rather ghastly about this aestheticization of an object at the center of an ongoing triple-disaster resulting in the deaths of nearly 20,000 people and the evacuation of over 200,000 more. Cinema Caravan’s indoor space in Hafenstraße continued this unnerving approach to Fukushima. A looped video showed Kuribayashi and Shizuno visiting the exclusion zone just after the earthquake. Only 10 kilometers from the still-melting reactors, they don wetsuits and surf where the 45-foot tsunami had just passed. This all felt insensitive at best—and at worst, a kind of brutal dancing on the graves of the dead and the miserable lives of the displaced.

What is strange is that the very origin of Cinema Caravan is deeply connected to the anti-nuke movement in Japan. They were motivated by one of the most important films of the movement, Kamanaka Hitomi’s Rokkasho Rhapsody (Rokkashomura rapusodii, 2006). Shizuno and Kuribayashi visited the Rokkasho protest site, and their caravan strategy was a response to the felt need to spread the word on this and other issues. They made multiple trips north to the disaster area to help victims of 311. This makes the video and Genki-Ro all the more perplexing. However, an essay from the collective commemorating the 10th anniversary of the disaster explains (starting with a question at the heart of Tokyo Reels):

Kuribayashi writes, “What kind of role does art have in relation to the conditions of the world? When I consider what could be the greatest energy of the energy problem, I realize it is humankind. It is the energy of humankind’s happiness and its wave motion. It is to find our way to arrive at the realization of that happiness. Is not the number one theme of humanity ‘Becoming Happy?’” (…) In these ten years of traveling to and from Fukushima, their stance changed from opposition/critique to sounding a warning, and finally from there taking one more step: Towards representations that invite people with positivity. Thus, they do not express themselves individually, but also work as a team. (Etsuko Kodaira. Fukushima, 10th Year—Takashi Kuribayashi + Rai Shizuno, 2021; adapted with my translation from the Japanese version)

In early September, Genki-Ro moved to an empty lot behind Sandershaus and next to the makeshift shelters of Argentina’s silkscreen collective Serigrafistas (see image above). Instead of installing their screen, they projected video art on the side of a tall, abandoned building. With the DJ spinning loud music and the bar serving up suds, everyone was hanging out and happy—an idyllic nongkron moment. I sat on the grass with Shizuno, with Hirabayashi flitting in and out of our conversation. We drank beer and shared our notes on documenta. I eventually expressed my reservations with Genki-Ro as we watched people walk through the tube, a few of them stripping to enjoy the sauna. Shizuno elaborated on the sentiment of the quote above. Cinema Caravan was committed to the anti-nuclear movement, but felt people were too afraid in the wake of 311. They insisted that after a decade, people needed to move beyond their paralyzing fears of radiation, to vitalize humanity by coming together in new, optimistic communities. I could not tune in. To me, this was simply too reminiscent of George H. W. Bush’s official campaign song, “Don’t worry; be happy!” (“In every life we have some trouble / But when you worry, you make it double”).

This brings me to the reason I focus on the political and aesthetic differences between Tokyo Reels and Cinema Caravan. It has something to do with their respective relationships to history, one diving into an archive to rethink the present and the other uncomfortably presentist. I can’t help thinking this helps explain their respective responses to the attacks on Tokyo Reels and other collectives.

Over the summer, the lumbung avoided direct confrontation with its critics and let ruangrupa interface with the press, politicians and bureaucrats. However, when a draft of the Scientific Advisory Panel’s conclusions started circulating and contained a call for the immediate dismantling of Tokyo Reels in its entirety, the lumbung decided it was time for action. Up to that point, there had been months of Zoom sessions to discuss the situation, strategize plans, and generally show solidarity with the artists who were being accused of anti-Semitism. Since nearly all were people from the Global South or diasporic, they most deeply identified with the targets of the attacks and naturally felt compelled to support their colleagues. In an empathic identification, many felt personally attacked even if they were not direct targets. This culminated in the creation of protest posters and the powerful statement, “We are Angry, We are Sad, We are Tired, and We are United.”

In reality, the lumbung was not completely unified. Cinema Caravan was one of the collectives that opted not to attend these Zoom sessions. Their signatures were painfully missing from the statement. As the other collective with Japanese connections, their absence was conspicuous and puzzling to many. On the lawn before glowing Genki-Ro, I asked Shizuno about this. He explained that from their point of view that statement was only about dividing people. Cinema Caravan was all about bringing people together and creating creative and optimistic communities. They could not sign such an aggressive and negative statement.

I pointed out that by refusing to even explain themselves, it left everyone to speculate over their silence. People wondered if they were aligned with the anti-anti-Semitism critics. For some, Cinema Caravan’s silence was not simply perplexing; it hurt a little. Learning this, Shizuno looked visibly unsettled, as this was hardly their intention and he said he would have to talk to his friends from the lumbung. He explained that their stance was essentially “non-poli.” This Japanese-English term indicates a brand of apoliticality peculiar to postwar Japan, a kind of phobia regarding militant movement politics, which grew out of the violent inter-sect warfare of the 1960s and 1970s. All the lynching of that era gave way to a debilitating “non-poli” ethos that resulted in a bad rep for political activism among subsequent generations. One wonders if this is why Cinema Caravan’s younger collective members could not readily identify with the post-colonial condition of their fellow artists, and the very pressing situation of the Palestinians in documenta fifteen.

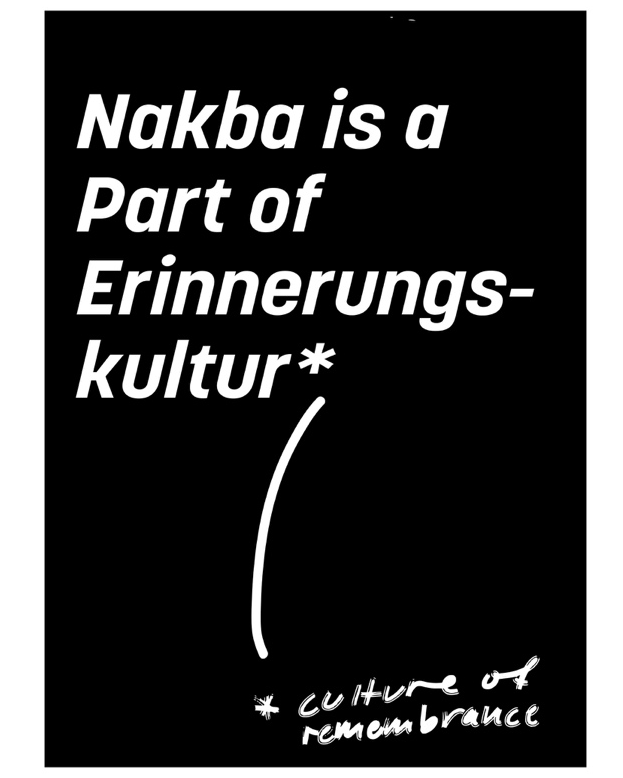

If this is the case, it suggests something about the stakes of historical memory. The fervor of the anti-anti-Semitism commitments of the Germans is both annoying and admirable. While filled with contradictions and laced with hypocrisy, there is no question that the passions stirred in Kassel are connected to a serious commitment to taking responsibility for the horrors of the 1930s and 1940s. At the same time, it was endlessly frustrating that those same commitments led to definitions of anti-Semitism that rubbed out the difference between race and state, dissolving any ground for critique of the Nakba—let alone present-day state violence. This, in turn, resulted in an insensitivity around race and colonialism and the artistic, critical and archival practices of the Palestinian lumbung members.

On the other side of the world, Japan famously sidestepped issues of war responsibility and their long history of imperial violence in Taiwan, Korea, and the rest of Asia. Over a half-a-century of focus on Japanese suffering during the war, combined with the insular comforts of economic development, have led to a kind of debilitating historical lack-of-memory. Put simply, while the memory politics of Germany were causing incredible pain and anxiety among the artists, the very different politics of forgetfulness enabled Cinema Caravan to sidestep a sense of responsibility—in the face of the triple disaster or the need for solidarity in the lumbung. Despite coming from a country responsible for the colonization of its neighbors, the imperial seizure of nearly the entirety of Asia, and a series of wars snuffing out some 25 million lives, one worries that Cinema Caravan’s non-poli stance was ultimately possible because of an evacuation of memory that rendered them oblivious to the post-colonial conditions of their fellow artists.

This is a small episode in a summer filled with scandals designed to smear artists and tarnish the reputation of documenta fifteen—attacks that were too often tainted by ignorance, arrogance, and even racism and violence. Unfortunately, all this unduly consumed the energies of the lumbung and the attention of the press. Having said that, over 700,000 visitors explored documenta, confronted “other ways of art-ing,” conducted their own nongkron, and tuned into the joyful and inspiring accomplishments of ruangrupa and the 1,500 artists of documenta fifteen.

Markus Nornes (website), a film scholar, curator, and maker, is Professor of Asian Cinema at the University of Michigan. He is mainly known for his writings in three fields: Japanese cinema, documentary, and film translation. Nornes worked as one of the first programmers at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, and has been an active film curator for over 30 years. He serves on the boards of various journals, and regularly sits on juries at international film festivals, has organized over a dozen international conferences, and has delivered over 100 lectures the world over. His latest book is Brushed in Light: Calligraphy in East Asian Cinema, which is open acces.

What did you learn at documenta 15? is an open-ended issue edited by Dóra Hegyi, editor of Mezosfera, curator, and project leader of tranzit.hu Budapest and Gyula Muskovics, independent curator and artist based in Budapest. If you would like to contribute, please submit your proposal, including a 200-word abstract and your short bio in English at office@tranzitinfo.hu.