At this moment of history, biennials seem to be a necessary evil. They have been challenged, contested, transformed, and critiqued. In retrospect, the Arab Biennial as a project has been overclouded by its politics and seen as a failure. Nevertheless, the genealogy of the biennial has its roots in a historical necessity that started through an artists’ initiative. The formation of the General Union of Arab Plastic Artists (al-Ittihad al-‘amm li-l-fannanin at-tashkiliyin al-‘arab) in 1971, registered Arab artists’ position and strong need for a shared forum and unity. The awareness of their fragmented existence within what has been argued throughout most of the twentieth century as a transnational collective strength in the form of pan-Arabism, was manifest in their need for better representation. As their contact increased through robust print media and scholarship programs, their desires for a stronger presence in the art scene equally intensified. Moreover, within the plethora of creative activities across the region, several moments of intense overlapping discussions had signaled parallel, if not intersecting interests and concerns.

Equally, as pan-Arabism rhetoric climaxed, Arab artists’ work became more interactive. More importantly, the cultural crisis which accompanied the 1967 Naksa (Arab armies rapid loss to Israel) added new demands on them. Correspondingly, a proliferation of cross-regional conversations and debates erupted. They tackled topics that centered on the properties of good art as well as new art practices and contemporary theories appropriate for their moment. Their intention was to explore and define the role of the visual arts in the making of the future Arab culture. Moreover, this collective of artists was in many ways modeled to parallel the various other Arab unity initiatives of the time, such as the United Arab Physicians, United Arab Engineers, and United Arab Writers. Their position also corresponded to certain political initiatives that centered around regional unity. In April 1971 the Federation of Arab Republics uniting Egypt, Libya, and Syria was announced and was effective from 1972 to 1977.

One could argue that the formation of the General Union was also a response to an earlier, failed attempt to present a united front by the Arab League to organize an Arab Artists Conference. Instead, the latter attempt was spearheaded by well-known and active individual artists who acted upon the personal need to unite. The Iraqi artist Jameel Hamoudi was designated to take a trip around the major cities of the Arab world to discuss the initiative. In the summer of 1971, a small group of artists from Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon met in Beirut and collectively drafted the founding statement of the Union of Arab Plastic Artists. In December of the same year, the First Arab Conference of Fine Arts (al-Mu’tammar al-‘arabi al-awwal li-l-funun al-jamila) was organized by the Syrian Association of Plastic Artists in Damascus. The program of the conference included several papers by artists Mahmoud Hammad and Fateh al-Moudarres, along with a number of other major artists, discussing a range of topics that included the current conditions of Arab artists in the various Arab cities; positions of Arab artists and Arab art within twentieth-century art, as well as in relation to Arab and other cultures; and the role of art and artists (in terms of duties and obligations) in the struggles of the Arab world.

The conference culminated in the proclamation of a General Union of Arab Plastic Artists as an umbrella organization with headquarters in Damascus that encompassed chartered, national associations. The Founding statement was ratified by seven artists as the Union’s first committee members, representing seven countries that included, Iraq, Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Lebanon, Kuwait, and Sudan, with the hope that in their next step, artists from the following countries would join: Jordan, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria. The Palestinian artist Ismail Shammout was announced as its first Secretary General.1 Four of the committee members were appointed as representative at UNISCO, the Arab League, The Arabian Gulf countries, and the al-Maghrib al-Arabi (North Africa). It is clear that the ideological constitution of the Union’s board reflected the political affinities and desires of the time, with the centrality of the Palestinian issue.

The main goal for the collective was clear in that it aimed to unite scattered individual creativities into a strong cultural and civilizational front.2 The objectives of the Union included the following: to provide continuous opportunities for Arab artists to meet and reflect on shared issues; provide a free and supportive environment for Arab artists to be creative without financial or political restrictions; enrich cultural and artistic exchange among Arab artists and facilitate an ease of movement for the artists and their works in and around the Arab world; organize regular (biennials) and traveling exhibitions at the regional and international level; organize informative and educational programs for the artists and Arab audience; to forge cultural and institutional exchanges worldwide; and lastly, to ensure an Arab presence at all and any world events.

Nevertheless, its political role was also clearly argued. In the conclusion of his speech during the first conference, Al-Moudarres declared:

It is the duty of the Ministry of Culture and Information, the Arab League, and the proposals legislated by the people’s assemblies to consider artistic work as an important component of the Arab nation’s battle. I hereby affirm that the program of the governments of Western Europe and North America includes the total eradication of the Arab nation, because we represent the only wall of resistance before Africa. The demise of the Arab nation would make it easier for the West to inaugurate a long era of modern economic colonialism in Africa.3

The Union thus, in various ways, positioned itself as an official body of representation under state patronage that quickly moved the initiative from an artist collective concerned with aesthetics and exhibitions with a focus on unity to an equivalent to a semi-political party, which would consequently cause the Union’s rapid demise.

Subsequently, the headquarters of the Union shifted from Damascus to Baghdad over the years 1972-73. There is no denying that the Ba’ath Party in Iraq found an opportunity within these regional developing sentiments to position Iraq as a regional leader on an intellectual and artistic level, as well as to garner popularity and domestic support for the party. The revenues that followed Iraq’s nationalization of its oil industries in 1972, allowed it to sponsor (lavishly) diverse initiatives, giving the Ba’ath Party the space to navigate its own perceived superiority over the two other major players on the scene: Egypt’s Nasser prominence, and Syria’s own Ba’ath Party. Iraq’s Ba’ath party’s aim was to reap full control and become the pan-Arab movement leader. Both Iraq and Syria were versed in the Arab nationalist rhetoric that was manifest in the state-sponsored art events: in April 1972, the Iraqi Ministry of Information organized the Yahya al-Wassity Festival (Mahrajan al-Wassity) in Baghdad, and in the same year in Damascus, the Syrian Syndicate of Fine Arts hosted the First Arab Festival of National Plastic Art (al-Mahrajan al-‘arabi al-awwal li-l-fann al-qawmi al-tashkili). It is within this discourse that we must understand Iraq’s (and Syria’s) support for the arts and its sponsorship of its infrastructure. Nevertheless, that does not in any shape or form negate the accomplishments of the artists or their own aspirations in taking advantage of the circumstances whether they agreed with the Ba’ath principles or not. On the contrary, we should look at it as a moment when goals of the two aligned.

In April 1973, Baghdad hosted the first conference of the General Union, and distributed by newsletter the ideological framing statement, “Art Inspired by the People, Struggle, and Liberation in the Trilogy of Heritage, the Present Moment, and Contemporaneity.” The statement started with:

Art in general, and Arab plastic art in particular, was never isolated from the movements of society, history, and the epoch. If Arab plastic art—in terms of heritage, the present moment, and contemporaneity—is a product of Arab society, with its rich and diverse civilization, that has over long historical eras enriched human civilizations and bestowed abundance upon them, it is also the product of the new Arab society that faces chronic imperialist pressures, such as deepening divisions through a belligerent, reactionary rightist expansion that conspires and helps to implement it. Arab plastic art is also a product of this Arab society facing, at its core, attempts to erase its Arab identity and civilization, as well as its very existence, especially where the pivotal issue in the struggle for Arab liberation is concerned: namely, the issue of Palestine.

Since contemporary Arab plastic art as a reality, along with its problems and aspirations, is the central subject of research and discussion of the First Conference of the General Union of Arab Plastic Artists to be held in revolutionary Baghdad this coming April 20 to 24, under the auspices of President Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr, the topics “Heritage and the Contemporary” and “The Role of Art in Crucial Arab Issues” are dialectically linked to that main subject.4

The title and language of this openly ideological statement specifically reflected the criticality of the Palestinian struggle as situated within a Third Word frame of reference that continued to be used to charge emotions in the Arab world throughout most of the second half of the twentieth century.

Today, the unity of the Arab struggle for liberation is taking on exceptional importance on all levels.5

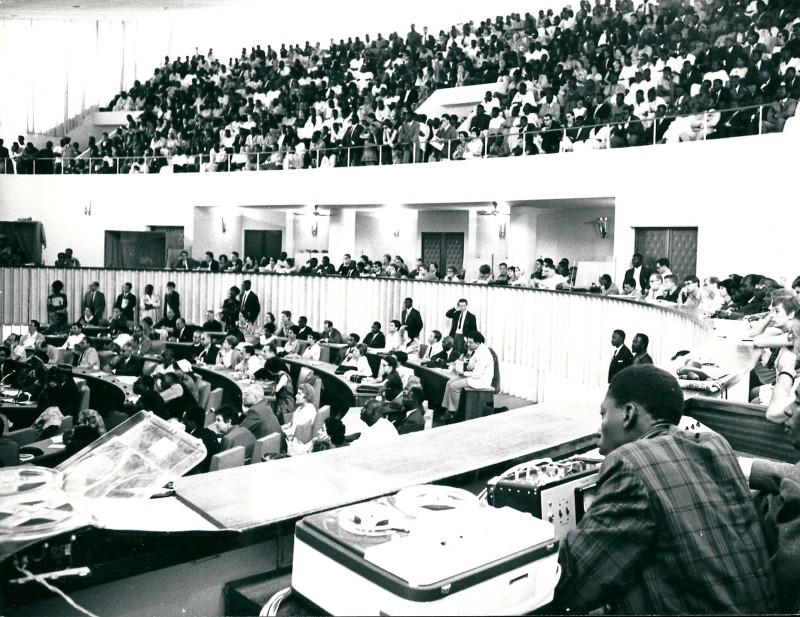

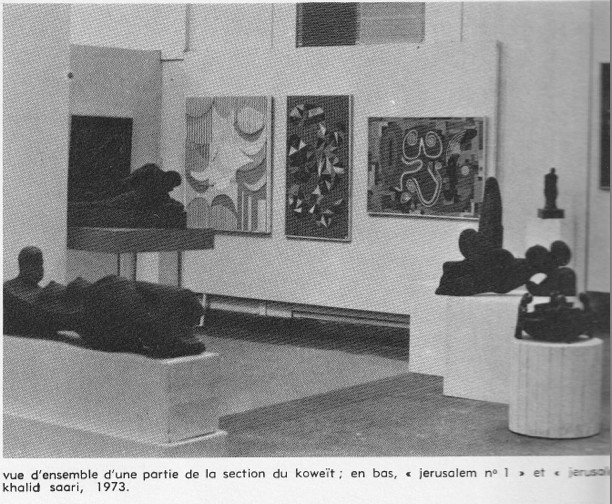

This was probably also why Shammout was chosen to be the first Secretary General, who would play a pivotal role in organizing the Union’s first biennial. It was in March 1974 that the General Union launched the first Arab Biennial in Baghdad. The second took place in Rabat, Morocco in December 1976, and a third less celebrated one in Libya.6 In accordance to the Baath Arabization policy, the Arabic naming was used instead: Ma’radh al-sanatayn al-‘arabi al-awwal (The First Two-Year Arab Exhibition). The biennial featured work from fourteen countries: Algeria, the Democratic Republic of Yemen, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Tunisia. Palestine was represented by the Palestine Liberation Organization with its own pavilion as an equal to other states.

“Arab,” a term that remains contested today for various reasons, I have argued elsewhere reflects a negotiated formation of an articulate and performative cultural identity that encompasses the multiplicity of difference in the form of ethnicities, sects, languages, that are the rich nature of the region.7 This cultural notion has preceded challenges and attempts of political unity.8 Nevertheless, the mediation of specific modern Arab imaginary from within the destruction of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, within the smoke of colonial threats and territorial restructuring, was a necessity for a distinct collective bloc, which explicitly allowed for an imagination of unities of sorts by the new nation-states during the Cold War era. However, within the context of the 1970s, the term was invoked on a more determined political identity. The notion had been circulating earlier as a way of forging a visual identity cross regional imagination and expressed decolonized negotiations of self in relation to internal development but equally channeled the legacy of the Bundung of 1955, the Tricontinental Conference of 1966 in Havana, and the ensuing Non-Aligned Movement, in which Egypt, Syria (United Arab Republic), and Iraq had partaken.

In the Forum convened along with the biennial, Shammout who acknowledged challenges, logistical and otherwise, stressed its positive results.9 Speakers invited to contribute to the forum expressed a multitude of sentiments that were equally critical as well as self-congratulatory. Badreldin Abou Ghazi [Egypt] argued:

First of all, why the first Arab Biennial? It seems to me that the inclination in calling for the organization and production of this exhibition was to break down the barriers that kept contemporary Arab artists in different countries of the Arab homeland isolated from one another, to endeavor to identify the best work of art in every Arab country, and to bring artists and work together in a spirit of cooperation. It may be that the exhibition has taken the name biennial and Arabized it. But even if we Arabize the name, we still need to Arabize the goal within our consciousness. For the notion of a biennial is an imported one that emerged from completely different concerns, and in societies very different from our Arab societies.10

Despite of acknowledged limitations, the Baghdad biennial was accepted by most artists and critics across the region as a refreshing and worthy experiment positioned to enrich art production in the Arab world. What is most interesting is the debate around the format of the biennial that it instigated. In a manifesto issued by the Moroccan Association of Plastic Arts on the occasion of the biennial, they cautioned that the format of the biennial was not avant-garde enough for what the Union had hoped to accomplish:

We hope that this first Arab Biennial will not follow the example of Western biennials that consist primarily of grouping professional artists together in a dull exhibition, similar to any commercial exhibition where the laws of supply and demand entirely determine which characteristics a production should adopt at a later stage. As witnesses of Arab reality, and wishing to discover its future concerns, we are convinced that this gathering of Arab plastic artists is too important to be merely an opportunity to take stock of abilities or talents. The next encounters should aim to focus our energies in order to mobilize the Arab peoples and put them on permanent alert.11

In a special issue of al Thaqaffa al-Jadidah dated March 1, 1977 that presented a roundtable discussion among three of Morocco’s leading artists instigated primarily by the biennial, Mohammed al-Melehi, Farid Belkahia and Mohammed Chebaa went as far to criticized the concept of a biennial as a dying European official national representation with the first Venice Biennial initiated under Mussolini, promoting a competitiveness akin to that of the Olympics. In their opinion, the biennial is a failed project in principle. Nevertheless, they cited added challenges for holding the second biennial in Morocco that included the country’s lack of infrastructure and adequate support as well as the bureaucracy that delayed all preparations.

On the other hand, Moroccan artist Fouad Bellamine in an interview in 1978, criticized the Arab Biennial as being unworthy to be named a biennial. He argued that it was a last minute development without much panning and that with the exception of the Iraqi and Moroccan Pavilions, were mediocre. He argued that what the two had “in common was the foresight to present works that could speak to the future without in any way disowning their cultural heritage.”12

In fact, the planning of the second Arab Biennial in Rabat instigated many controversies. A second art group named the Association of Moroccan Plastic Artists was initiated in Casablanca by A. Ghani Belmaachi. Abdessalam Guessous, Abdelhay Mallakh, and Omar Bouragba to challenge the role of the official Moroccan Association of Plastic Artists that had assumed the leading role in affiliation with the General Union of Arab Plastic Artists in planning the biennial. The new group expressed dissatisfaction with the status quo in Moroccan art. Thus in response to what they evaluated as the official response, they planned a parallel exhibition they titled “Twenty Years of Plastic Art in Morocco.”13

Moreover, the quality of works of art accepted in the biennial were criticized by other artists as well. The Iraqi artist Dia Azzawi who had not participated in the first biennial in Baghdad because of military conscription, argued for the positive effect of the Biennial in Baghdad for presenting good examples of modern negotiations of the national and local to Arab artist that helped aid them in their movement away from European models, which in turn, spoke of a movement towards their shared goals. Nevertheless, he argued that it was neither competitive nor critical in relation to aesthetics or the production of good art but rather presented the work in reductive contexts of nations incapable of crafting a united vision adept to negotiate the proposed Arab unity.14 However, in relation to the Rabat Biennial, in which he participated, he criticized many of the participating artists for not abiding by the theme of the biennial, which was Palestine, and thus contributing to its failure and that of a united front.

Despite of the various critiques, controversies and challenges, the General Union of Arab Plastic Artists and Arab biennial have left an historiographic legacy, both positive and negative, that necessarily expresses its generational occupations, aspirations, and failures. Identity, the need to have a strong and distinct presence in a united front, and for their art to find its place within modernism, occupied the artists and intellectuals of the region for most of the twentieth century. The Union and its biennials also articulated the artists grappling and coming to term with both Arabism and world politics but mostly the primacy of Palestine as a marker of the Arab identity. This would continue to be discernible and negotiated in various other venues. The critique of the biennial by the Moroccan artists, in time, was manifest in a local format that the artists could call their own: the International Cultural Moussem Assilah. A forum that still continues, Assilah proved to be a more malleable and appropriate space of creativity that was as local as it was international in its reach. In 1981, al-Fann al-Arabi, the magazine of the General Union of Arab Artists, would dedicate space to celebrate Assilah’s success as well.

About the author

Nada Shabout is a Professor of Art History and the Coordinatorof the Contemporary Arab and Muslim Cultural Studies Initiative (CAMCSI) at the University of North Texas, USA. She is the founding president of the Association for Modern and Contemporary Art from the Arab World, Iran and Turkey (AMCA). She is the author of Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, University of Florida Press, 2007; co-editor with Salwa Mikdadi of New Vision: Arab Art in the 21st Century, Thames & Hudson, 2009; and co-editor with Anneka Lenssen and Sarah Rogers, Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018. She is the curator of Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, Interventions: A dialogue between the Modern and the Contemporary, 2010; co-curator of Modernism and Iraq, Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, 2009, and curator of the traveling exhibition, Dafatir: Contemporary Iraqi Book Art, 2005-2009. Her awards include: Writers Grant, Andy Warhol Foundation 2018; The Presidential Excellency Award, UNT 2018; The American Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TAARII) fellow 2006, 2007; MIT visiting Assistant Professor, spring 2008, and Fulbright Senior Scholar Program, 2008 Lecture/Research fellowship to Jordan.

Notes

- Shammout was also a co-founder of the Union of Palestinian Artists, established in 1971. ↩

- “Bayān al-Hayʾa al-Taʾsīsiyya li-l-Ittiḥād al-Fannānīn al-Tashkīlīyīn al-ʿArab,” Fann (Summer 1986): 7–10. Translated from Arabic by Dina El Husseiny. In Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, eds. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, and Nada Shabout (New York: MoMA 2018), 335. ↩

- Fātiḥ al-Mudarris, “Al-Fannān al-ʿArabī fī Ḥuqūqihi wa-Iltizāmātihi,” in al-Muʾtamar al-ʿArabī al-Awwal li-l-Funūn al-Jamīla (Damascus: Niqābat al-Funūn al-Jamīla, 1971), 115–18. Translated from Arabic by Dina El Husseiny. In Ibid., 341. ↩

- “Fann Yastalhamu al-Jamāhīr wa-l-Maʿrika al-Taḥarrur fī Thuluthiyyāt al-Turāth wa-l-Ḥāḍir wa-l-Muʿāṣira,” repr. in Khāliṣ ʿAzmī and Nizār Salīm, eds., al-Muʿtamar al-Awwal li-l-Ittiḥād al-ʿĀmm li-l-Fannānīn al-Tashkīlīyīn al-ʿArab (Baghdad: Wizārat al-ʿIlām, 1973), 12–13. Translated from Arabic by Dina El Husseiny. In Ibid, 374–376. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- There is unfortunately no archival record I could find for more information about this iteration of the Arab biennial or a written critique as to why it has not been successful or acknowledged much. ↩

- See Shabout, Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics (Gainesville: Florida University Press, 2007); S. Mikdadi and Shabout, eds, New Vision: Arab Art in the Twenty-First Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009); and Shabout et al, eds., Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art. Exhibition Catalogue, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, Qatar (Milan: Skira Publisher, 2010). ↩

- In modern geopolitical terms, the “Arab world” is defined as a grouping of majority Arabic-speaking nation-states that range from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Gulf. ↩

- Nadwat al-ʿAdad – Ārāʾ fī Maʿraḍ al-Sanatayn al-ʿArabī al-Awwal,” al-Tashkīlī al-ʿArabī, no. 2 (March 1975): 5–15. Translated from Arabic by the editors. In Modern Art in the Arab World, 376-383. ↩

- Ibid., 377. ↩

- Première Biennial des arts Plastiques à Baghdad: Manifeste de l’Association marocaine des arts plastiques.” Intégral, no. 8 (March–April 1974): 16–19. Translated from French by Teresa Villa-Ignacio. In, Ibid., 385. ↩

- “Entretien avec Fouad Bellamine,” Integral, no. 12/13. Translated from French by Teresa Villa-Ignacio, in Ibid., 411. ↩

- For the full manifesto, see “Manifesto of the Association of Moroccan Plastic Artists (1976), in Ibid. 408–410. ↩

- Azzawi, al-Alam al-Thaqafi in Dialogue with Azzawi, Critique of Rabat Biennial, December 1976. ↩